Neoliberals have consistently presented various “arguments” to justify privatization and contractualization of work. A common claim is that the private sector is “less corrupt” than the public sector, and therefore, more efficient. Every government has issues with corruption, that’s true. There are always opportunists misusing their power and authority to enrich themselves instead of working for the public. This applies to every country, not just India. In the U.S., legalized corruption is euphemistically called “lobbying.”

The issue is that many people don’t see the corrupt behavior of the private sector as wrong. Privatization is legalized corruption; it involves transferring public assets to the private sector without the consent of the stakeholders, primarily the workers.

The idea that privatization leads to less corruption has been debunked several times, most recently with the various exam scandals in India.

In fact, much of the large-scale corruption involves collusion between the private and public sectors, with the private sector seeking control over the state and its resources. Every recent large-scale corruption scandal in India, such as the Bofors Scandal, 2G Spectrum Scandal, Coal Block Scandal, Rafael Scandal, and more recently, the Electoral Bonds Scandal, has involved the private sector.

In each of these cases, the private sector (including the foreign sector) has sought control over the public sector and its resources. Typically, the private sector steals two main things from the public sector. First, public money; for example, in the 2G Scam, the private sector paid far less than the actual price of the resource they were seeking. Second, public resources; again, in the 2G Scam, it was control over radio spectrum, which is supposed to be in the public domain.

There are ways corruption is obfuscated too. For example, with the Electoral Bonds scandal, there was no direct loot of the public sector. The private sector was, in fact, ‘donating’ to various political parties. But it is clear what the donations mean: quid-pro-quo. The private sector ‘donates,’ and the public sector stops going after them for tax evasion and the like, or maybe provides preferential access to state resources. In both these cases, there is a net loss for the public with the private sector enriching themselves.

People often see corruption as small-scale bribery, like giving ₹1,000 to the police to avoid a fine for not wearing a helmet. They don’t perceive the need to bribe the private sector in the same way. The reason why the private sector has less of this kind of bribery is that they make you pay through the prices they charge, either directly or indirectly. A private sector telecom company doesn’t make you pay a corrupt bureaucrat ₹500; instead, they incorporate these costs into increased fees and fleece the state to gain access to radio spectrum.

Perhaps the most famous case of legal large-scale corruption was the 2008 Financial Crisis, where large bankers were given $29 Trillion by the U.S. Central Bank to prevent the collapse of the financial system. In a fair system, the state would have ensured that the workers were made whole, the bankers were thrown in jail, and their banks were nationalized. Instead, 2008 saw possibly the largest transfer of private sector losses onto the public ledger.

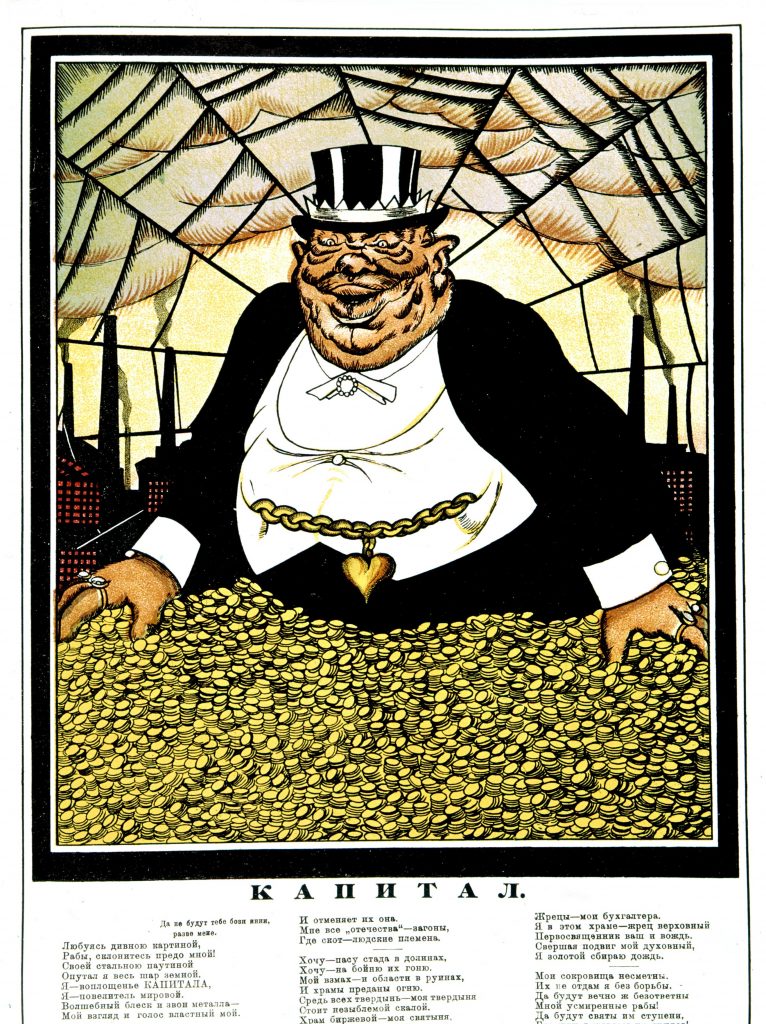

My point is that we shouldn’t view corruption merely as small-scale bribery. The big capitalists engage in corruption on an industrial scale, a scale so vast that even they can hardly comprehend it. The petty bribery most of us encounter in developing countries is nothing compared to this massive corruption.

And that isn’t to say the private sector is immune to petty corruption either. The recent exam scandals saw privately contracted workers accepting bribes to provide answers to tests. These workers might make around ₹20,000 a month, while the businessmen involved make millions and billions. There is no comparison.

I want to end this blog with this video on Europe’s energy scam, the privatized energy market in India is very similar.

That’s all.