Recently, the Reserve Bank of India included credit/debit card spending under the Liberalized Remittance Scheme (LRS). This effectively brings credit/debit cards under the $250,000 annual foreign currency purchase limit. No resident can send more than $250,000 a year using their cards. Keep in mind, this limit applies to all categories of foreign exchange purchases, not just card transactions. For example, if you send $100,000 to a relative abroad, you can only purchase $150,000 worth of foreign currencies using your cards. To sidestep this limit, you can use your relatives’ accounts.1

In addition, there is a Tax Collected at Source (TCS) of 20% for foreign currency purchases via card beyond ₹700,000. This isn’t a ‘tax’ per se; the government wants you to report the spending on your tax return to get the 20% back. It is only a tax if you don’t claim it back. In a way, you are giving an interest-free loan to the government.

Why is the government doing this? Whenever you send money abroad, someone else has to be willing to hold your currency, in this case, Indian Rupees, in exchange for the currency you seek, such as U.S. Dollars. This transaction occurs in modern times through foreign exchange markets. The problem is that whenever foreign currencies are purchased in these markets, the domestic currency depreciates.

What happens when the currency depreciates? Imports become costlier, and exports become cheaper. The extent of this depreciation depends on the elasticity of the exchange rate.

The issue is that currently, the U.S. Central Bank, the Fed, has kept interest rates high, resulting in outflows of capital from developing countries to ‘safe haven’ U.S. Treasuries. The RBI, in an attempt to prevent depreciation, is intervening in the foreign exchange markets to keep the Rupee stabilized at approximately ₹83 = $1. But how does it do this?

Let’s say an Indian commercial bank is facing excess demand for Dollars. It goes to the foreign exchange markets and purchases Dollars at ₹83 = $1. This creates an excess supply of Rupees in the foreign exchange markets, which would usually cause a depreciation in the exchange rate. To prevent this and keep the rate stable, the RBI intervenes by using its foreign currency reserves to buy Rupees, thereby draining the excess supply of Rupees and maintaining the exchange rate at its desired level.

he last part is the problem: the RBI is using publicly owned foreign currency reserves to subsidize a specific segment of the private sector. I’ve criticized this in my previous blog here.

The RBI is thus expanding capital controls to include cards. Capital controls are policies that restrict the free movement of capital (in this case, foreign currencies), either in terms of inflows or outflows.

India has capital controls, as do most developing countries. Before 2000, when India was in the process of liberalizing, there was the Foreign Exchange Regulation Act (FERA), which made unauthorized trading of foreign exchange illegal and punishable with imprisonment. In 2000, the Foreign Exchange Management Act (FEMA) replaced FERA, opening up India’s current and capital accounts. Indian residents gained much greater freedom to purchase and sell foreign currencies legally. Imprisonment was replaced with fines.2

The Liberalised Remittance Scheme (LRS) was introduced in 2004 to allow Indians to send money abroad without much paperwork. If you are sending smaller amounts of money abroad, you are likely doing it through LRS. There are conditions for sending money using LRS, the most important being that an individual can only send $250,000 in a year. If you want to send more than that, you’ll have to go the non-LRS route, which involves much more paperwork and requires RBI approval. In countries with very open capital/current accounts, usually developed countries like the U.S. or the U.K., no such restrictions exist.

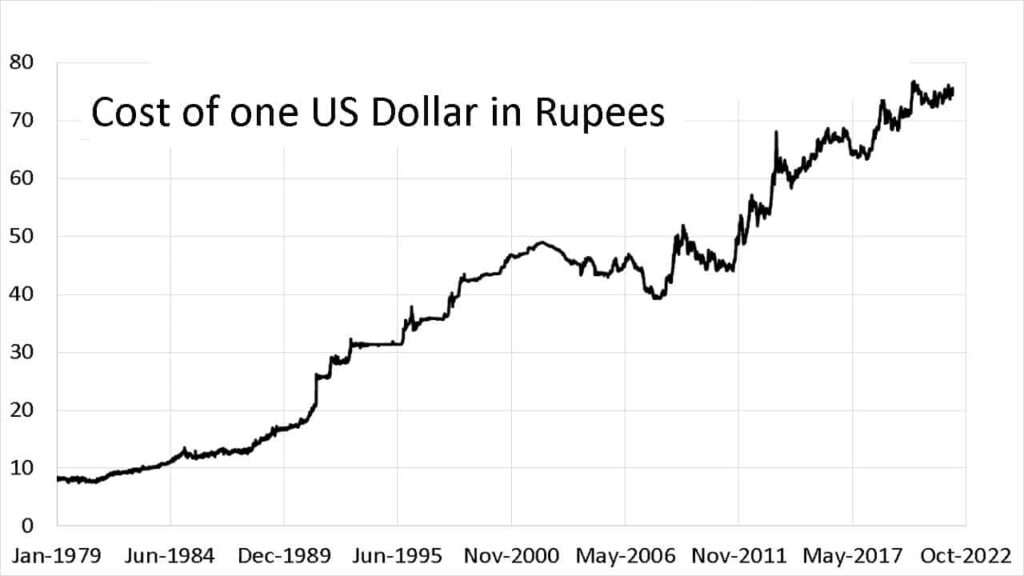

With capital and current accounts more open, the Indian Government lost significant control over exchange rates. Indeed, the RBI stopped fixing the exchange rates within tight bands with periodic devaluations in the 2000s. The 2000s saw massive capital inflows to India, with foreign investors from the West rushing in to invest in the now more liberalized Indian economy. This resulted in a significant appreciation of the Rupee between 2002 and 2007. In fact, the Indian Rupee appreciated from around ₹49 = $1 in 2002 to approximately ₹40 = $1 in 2008. This appreciation wasn’t inherently good. The RBI intervened during this period to keep the Rupee ‘undervalued’ because an appreciating exchange rate is not good for trade competitiveness. As mentioned previously, a weaker currency, while making imports expensive, also makes exports cheaper.

A similar effect occurred in China as well. Unlike India, China was running massive current account surpluses, which meant there was great demand for Chinese Yuan in the foreign exchange markets. However, the Chinese Central Bank, PBOC, kept the Yuan fixed very tightly at $1 = CN¥ 8.27 up until 2005. This was done to encourage exports so China could accumulate the foreign currencies it needed for development. In 2005, China allowed its currency to appreciate significantly, reaching $1 = CN¥ 6.82 in 2008. This shows that if a country has high demand for its currency in the international markets (due to capital flows or a current account surplus), it would see its currency appreciate in the absence of capital controls and Central Bank intervention.

Keeping the Rupee ‘undervalued’ is not the same as keeping the Rupee ‘overvalued.’ Currently, the Indian Rupee would depreciate if the RBI stopped intervening. This is unlike the early 2000s period when the Rupee would appreciate if the RBI stopped intervening. The issue is that the process of keeping a currency ‘undervalued’ is very different from keeping a currency ‘overvalued.’

In the early 2000s, the RBI intervened to prevent the Rupee from appreciating too much by purchasing foreign currencies and increasing its reserves. This intervention kept the Rupee ‘undervalued,’ promoting export competitiveness by making Indian goods cheaper in international markets.

Currently, the RBI’s challenge is to prevent the Rupee from depreciating. To keep the Rupee ‘overvalued,’ the RBI must sell its foreign currency reserves to buy Rupees, thereby supporting the currency’s value. This is more challenging because it depletes the RBI’s reserves over time, and maintaining this intervention can be costly and unsustainable in the long run.

India can keep its currency ‘undervalued’ by increasing the supply of Rupees in the foreign exchange markets, Rupee is its own currency and it has no limit on the amount of Rupees it can create. However, keeping the currency ‘overvalued’ is very different, in this case India has to intervene by draining its foreign exchange reserves or trying to attract foreign currency inflows (which it can’t in the current environment). Foreign exchange is a limited resource, India cannot create U.S. Dollars, only the U.S. Central Bank can. Thus, if the downwards pressure on Rupee continues for too long, RBI will be forced to stop its interventions because the drain on foreign reserves would be too high.

The only other way to maintain a stable exchange rate along with independent monetary and fiscal policy is through tighter and stricter capital controls. While bringing cards under LRS is a form of stricter capital control, it is clearly not enough to stop the downward pressure on the Rupee. The Indian Rupee reached new lows recently despite the RBI’s interventions.3

According to market participants, the RBI had intervened in the foreign exchange market via dollar sales, which prevented the rupee from further depreciation.

This goes back to the headline topic:

The new regulations are seen as part of the government’s broader strategy to curb excessive foreign exchange outflows and restrict high-value expenditures made through international credit cards.

Economic Times

The reason for such large outflows on international cards is not because of foreigners selling their assets, only domestic residents have credit/debit cards (typically). These outflows aren’t by foreigners but Indians. Indians (especially the top 1%) are purchasing foreign currencies by sending money abroad through cards (a capital account transaction) or purchasing goods and services abroad (current account transaction).

Why did such outflows rise exponentially in 2022? The RBI’s Rupee stabilization strategy was (and still is) giving wealthy Indians cheap access to foreign currencies, with the exchange rate staying at around ₹82 to 83 = $1, despite other currencies depreciating much more.

If the RBI stops intervening, the exchange rate will depreciate. This depreciation will result in lower demand for foreign currencies, and the RBI will no longer have to drain valuable foreign exchange reserves to keep the Rupee stabilized.

Would bringing cards under LRS lessen capital outflows? Sure, it will have some effect, but India still has very open capital and current accounts. Therefore, this change is unlikely to be enough to stop the depreciation. To do so would require much stricter control over capital flows, something the current government is unwilling to do because it would deter foreign investments.

I believe the RBI will eventually be forced to stop intervening, given the current conditions. I hope it happens sooner rather than later because precious foreign exchange is being wasted so the wealthy can send money abroad for cheap.

- https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/business/india-business/will-your-international-credit-card-spends-come-under-liberalised-remittance-scheme-soon-what-you-should-know/articleshow/108779552.cms ↩︎

- https://groww.in/blog/difference-between-fera-and-fema ↩︎

- https://thewire.in/economy/rupee-settles-at-new-closing-low-of-rs-83-66-against-the-us-dollar ↩︎