There has been considerable discussion in the progressive media in India and Bangladesh suggesting that the fall of the Bangladesh government was due to the student movement resisting “dictatorship.” I disagree.

The main reason for the collapse of the Hasina government was economic. People don’t randomly decide to rise up against governments; there is always a catalyst. The Awami League government stayed in power for over a decade because it had popular support. Bangladesh saw significant economic growth under its regime, which I believe was the primary reason, along with state repression, that there were no major protests against the government, until recently.

The reasons behind the government’s fall in Bangladesh are similar to those affecting India’s other neighbors, Sri Lanka and Pakistan. The escalation of the war in Ukraine in 2022, OPEC+ price hikes, and subsequent interest rate increases by the U.S. Federal Reserve squeezed the external sectors of developing countries.

Western institutions like the IMF and the World Bank pushed these countries toward export-oriented growth in exchange for assistance. Such growth models rely on external demand for goods and services produced by the country. The events of 2022 led to a decline in global demand, causing a squeeze on exports from these countries.

On the other hand, imports were also squeezed. How? First, the OPEC+ price hikes sharply increased the cost of crude oil in dollar terms, which most developing countries need to import. Additionally, the U.S. Federal Reserve raised interest rates to curb inflation by creating unemployment (which didn’t work well, but that’s another discussion). The impact on developing countries was severe: as interest rates rise, the gap between U.S. returns and those in emerging markets narrows. Investors also view financial assets in emerging markets as riskier, leading to massive capital outflows to “safe haven” assets like U.S. government bonds and gold. This phenomenon is known as “flight-to-safety.”

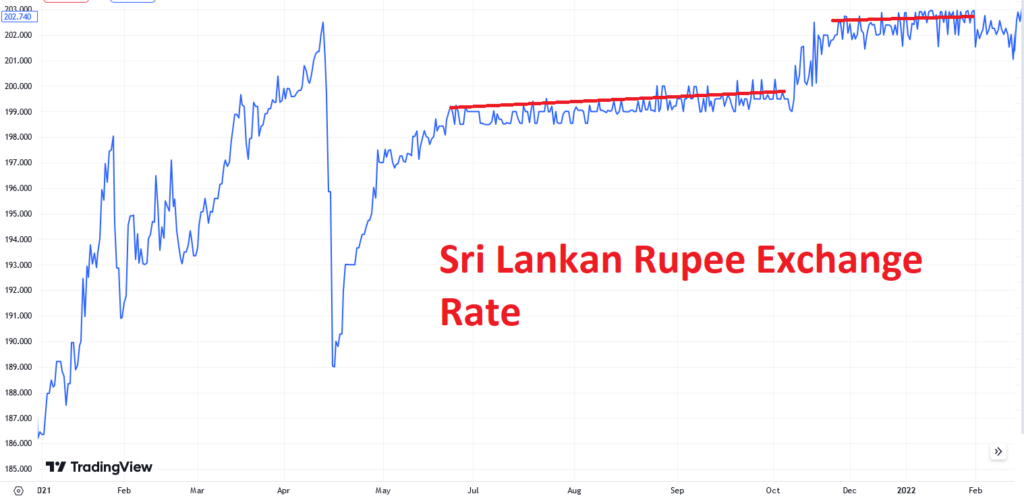

The outflow of foreign currencies put pressure on exchange rates in nearly all developing countries, particularly smaller economies like Sri Lanka and Bangladesh, as well as those with high external debt burdens, like Pakistan.

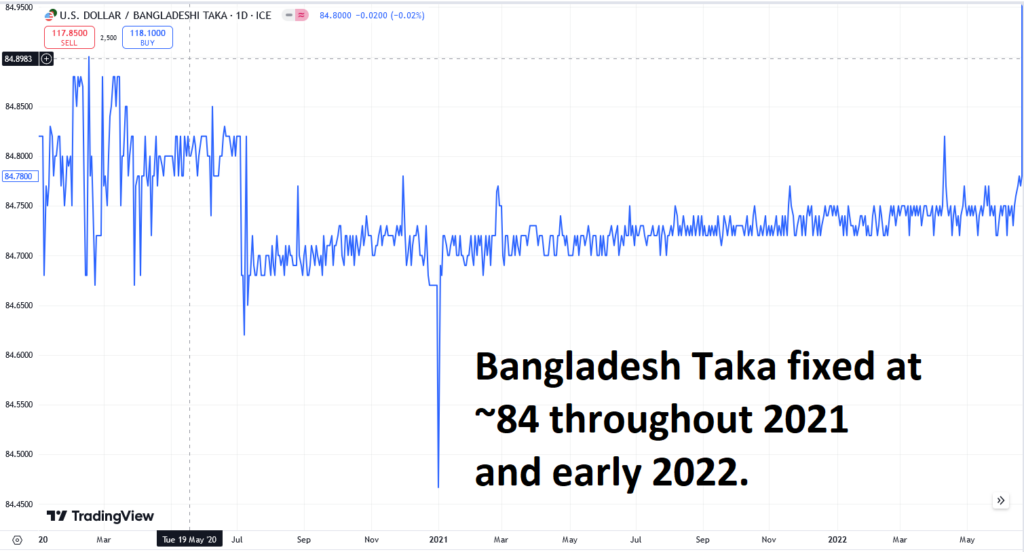

It’s also important to note that many of these countries tried fixing their exchange rates against the U.S. dollar to limit pass-through inflation. However, this policy has significant flaws, especially given that these countries maintain relatively open trade and capital flows.

Exchange rate stabilization of this kind benefits the rich far more than it helps the poor. In Bangladesh, illegal transfers of money abroad to avoid taxes and the hoarding of hard currencies were rampant due to lax enforcement of foreign exchange regulations. Such outflows could have been manageable under a fixed exchange rate as long as capital inflows were sufficient. However, when capital flows reversed, the Central Bank was forced to draw down its foreign exchange reserves to maintain the desired rate.

The Bangladesh government slowly depleted its foreign exchange reserves and had to seek IMF assistance. The private sector faced a severe dollar liquidity crisis, prompting the government to impose import controls to slow the drain. However, as mentioned earlier, Bangladesh’s controls were poorly enforced. The Bangladesh Bank eventually had to devalue the currency, which only temporarily eased the issue while causing a sudden economic shock.

A better approach would have been to let the currency float with minimal interventions. True, this would lead to greater exchange rate volatility, but it would also allow for more gradual adjustments compared to the sharp devaluations typically associated with fixed exchange rates. For instance, the Bangladeshi Taka experienced several sharp devaluations throughout 2022.

A floating exchange rate doesn’t preclude trade and capital controls. Nor does it prevent the government from rationing essential goods or implementing price controls. However, managing pass-through inflation via exchange rate control is often a blunt instrument, akin to raising interest rates to combat inflation, which can backfire by increasing interest payments on government debt.

Back to Bangladesh: reduced demand for exports, increased import costs, and their pass-through effects eroded the purchasing power of Bangladeshis, leading to lower aggregate demand. Economic growth slowed, while inflation and unemployment rose. The government’s disregard for its citizens and its reluctance to implement measures to prevent a decline in living standards for the poor led to widespread discontent. The recent elections with only 40% turnout didn’t help either.

The quota movement was a catalyst. Quotas are fundamentally economic, meant to distribute limited resources among the most marginalized groups. Many viewed the quota for the children of liberation fighters as unfair since that wasn’t the basis of their marginalization. In an economic environment marked by high unemployment and inflation, where people compete fiercely for limited government jobs, the quota verdict must have felt deeply unjust. The Hasina government’s refusal to heed public sentiment and its excessive use of force only worsened the situation, though it wasn’t the root cause.

Once the courts ended the excessive quota, the unrest seemed to subside. However, this also weakened the government. This set the stage for the second wave of protests, where the demand shifted from removing quotas to removing the government itself. The protests lacked a coherent ideology or goals beyond ousting Hasina. Such movements can be easily co-opted by reactionary elements seeking to further their own agendas without genuinely changing the status quo.

The attacks on Sheikh Mujibur Rahman’s monuments, buildings, and statues indicate that the protesters were not merely “angry” but that reactionary forces were involved. The same applies to the attacks on minorities. Less than 48 hours after Hasina stepped down, the BNP began holding large rallies with elaborate banners and full organization. It’s hard to believe that the opposition was unaware that Hasina would be ousted by the military.

I don’t believe much will change for the working-class people of Bangladesh. The interim government is led by a pro-U.S. neoliberal banker. There’s no trade union representation in the advisory cabinet. The political vacuum created is likely to be filled by the BNP in the coming elections.

That’s all.