There has been much discussion in the liberal business media about a slowdown in bank deposits, with claims that this is detrimental because it reduces credit creation.1 The stated reason for this slowdown is that people are investing in the stock market and mutual funds instead of keeping their money in banks.

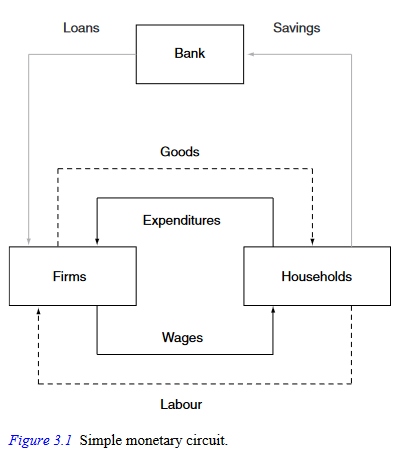

This argument is based on the flawed Loanable Funds theory, which posits that banks must first collect deposits to increase their reserves before they can lend out money. According to this ‘theory’, if a bank receives, say, ₹1, it can lend out a multiple of that amount, such as ₹100, to generate more profits. This is referred to as the money multiplier mechanism.

However, there is a problem: where do deposits come from? If banks can’t give out loans before they get deposits, then where do deposits come from?

The reality is that banks don’t need deposits to make loans. They do, however, need to create loans in order to make profits, which come from making loans at a higher rate than the cost they obtain money for.

So what is the process of getting a loan? You go to a bank, ask for a loan, and the banker checks if you are creditworthy. If they consider you creditworthy, they create a new loan account and generate money out of nothing. The banker doesn’t reject your loan application because they are short on reserves. In fact, the departments handling credit and reserves are separate. The bank first makes a loan and then secures the reserves it needs later if it is short.

Where does the bank obtain reserves from? It has several options. It can try to obtain loans in the interbank market, where commercial banks lend reserves to each other. If it can’t get reserves from the interbank market, it can ask the Central Bank for reserves through the discount window facility, usually at a penalty. The Central Bank of a sovereign currency-issuing state can always provide banks with the reserves they need. However, if the Central Bank sees that a bank is not sufficiently capitalized, it may refuse and take over the bank instead.

The purpose of reserves is to make sure interbank payments clear (and to meet legal requirements). Reserves are stored as digital entries in accounts commercial banks have at the Central Bank. When you transfer money from Bank A to Bank B, the reserves (an asset) of Bank A decrease, and the reserves of Bank B increase. Similarly, the deposits (a liability) of Bank A decrease, and those of Bank B increase. There is no net change in the assets/liabilities of either bank.

Also note that reserves are a liability of the Central Bank—this is government money. The deposits you hold at a bank are liabilities of the commercial bank.

So, what are the ramifications of slow deposit growth on commercial banks in India? None. The banking sector will be fine as long as people can repay their loans. The reason for low credit demand isn’t because banks don’t have enough money to lend but because people don’t want loans for various reasons.

“The currently dominant modeling framework is what we have labelled the intermediation of loanable funds (ILF) model. We have shown that the ILF representation of the accumulation of bank deposits does not correspond to real-world deposits of private financial instruments (or of central bank money) at banks. The reason is that any financial instrument only has value because the deposit already exists at another bank.”

“The main constraint is banks’ own and their customers’ expectations concerning the profitability of additional loans. If these expectations are volatile, then financial sector balance sheets must also be volatile.”

Bank Of England2

Just think about what happens when you buy a stock. You get a share in Company E for ₹1,000. One of your assets, cash, decreases by ₹1,000, while another asset, the share of Company E, increases by ₹1,000. The balance sheet value of the share will fluctuate depending on the share price of Company E.

When the transfer of ₹1,000 is made by the bank, your bank, Bank A, sees a reduction in reserves of ₹1,000, while the bank account of Company E at Bank B sees an increase in reserves by ₹1,000. One bank loses reserves while the other gains reserves, so the net effect on the banking sector is zero.

So, what does the increased credit growth indicate?

As I showed, slow deposit growth doesn’t mean banks are going to go bankrupt. It simply indicates that demand for credit is higher. The real question is whether the credit is being used to inflate asset prices or being invested productively. Can these loans be repaid? Are the banks’ underwriting standards high enough to ensure that defaults are low and don’t result in the forced closure of banks?

Note that this is a completely separate issue from banks not being able to lend due to low deposits. Credit growth is determined by the demand for loans, and the demand for loans is driven by aggregate demand backed by the ability to repay. For example, if consumers want a home and can afford to repay the loan, they will seek a home loan. Similarly, if a capitalist sees an opportunity to make sufficient profits by purchasing machinery, they will take a loan for that purpose.

India has a myriad of issues, such as poverty, unemployment, disease, malnutrition, and illiteracy, but low bank deposits is not one of them.

That’s all

- https://indianexpress.com/article/explained/explained-economics/banks-slow-deposit-growth-markets-9551518/ ↩︎

- https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/-/media/boe/files/working-paper/2018/banks-are-not-intermediaries-of-loanable-funds-facts-theory-and-evidence.pdf ↩︎