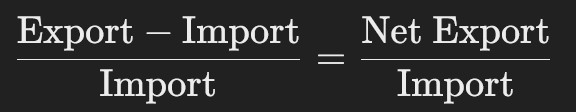

Recently, U.S. President Donald Trump announced import tariffs on nearly all countries.1 Almost every country is affected by it. What’s striking, however, is the manner in which the tariff rates were calculated. The banner shown by President Trump during the announcement read, “Tariffs Charged to the U.S.A. including currency manipulation and trade barriers.” One would look at this language and think that the administration used complex formulas to decide the tariff rate on a country-by-country basis. Maybe they looked at how much central banks were intervening in the forex markets? Maybe they looked at other countries’ tariffs. The reality, however, turned out to be much stupider.

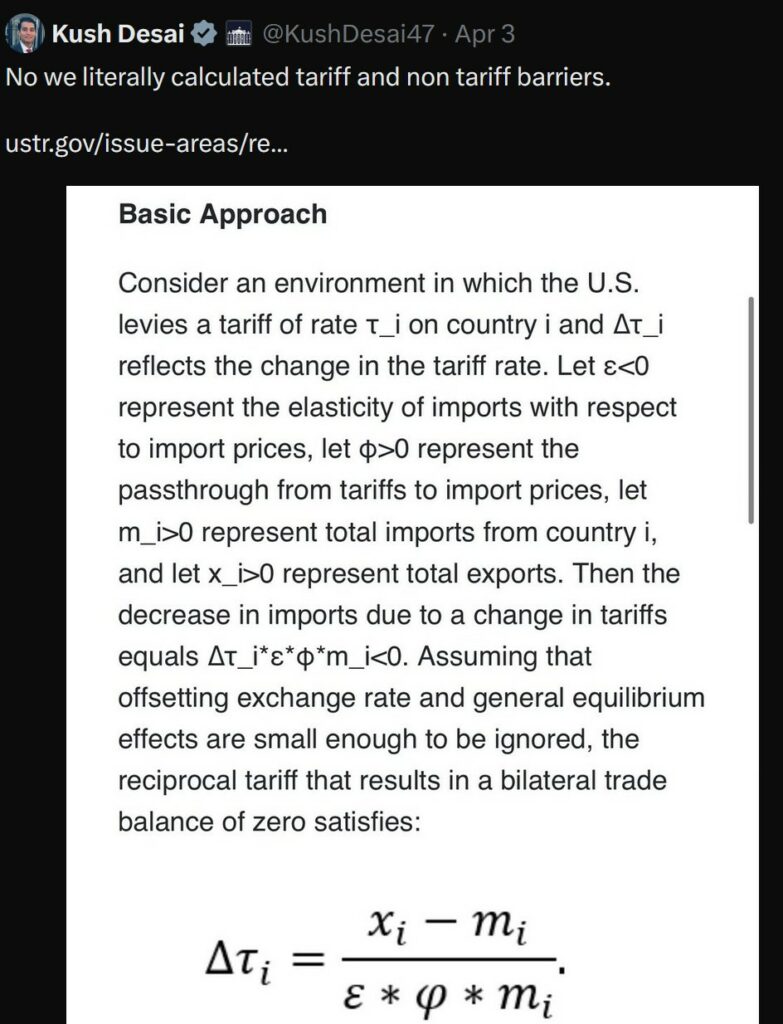

The tariffs were not calculated on the basis of “currency manipulation and trade barriers,” but simply by calculating the ratio of net exports to imports. This was the “explanation” provided by the White House deputy press secretary:

The Greek symbols make it look like a much more complex, refined formula than it actually is, but if you look at the USTR.gov site, you’ll find the values for the aforementioned Greek symbols.2

“The elasticity of import prices with respect to tariffs, φ, is 0.25.”, “The price elasticity of import demand, ε, was set at 4.“.

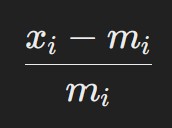

You only need basic algebra to figure out that 0.25 is equal to 1/4, and that 1/4 × 4 equals 1. So, ε and φ cancel out, and the only remaining term in the denominator is mᵢ. The values of ε and φ are kept constant for all countries, so there’s really no need to include them; unless, of course, you want to make it appear more complicated than it actually is.

Once you take the fluff out, you’ll find that xᵢ is actually Exports, and mᵢ is actually Imports. So, the formula really ends up being:

Or if you want less letters:

So, it’s really just the trade balance with any particular country, and the tariff was set at half the percentage of whatever the “formula” spat out. There is also a base rate of 10% which applies to all countries, whether they have a trade surplus or a deficit with the U.S.

Thus, it is clearly not a “Reciprocal Tariff,” as the Trump administration claims it is. This is how America’s own puppet state, Israel, ended up being tariffed at 17%, simply because they have a trade surplus with the U.S.

And that’s how Heard and McDonald Islands, two uninhabited islands, ended up being slapped with a 10% tariff, even though no one lives there. They simply, blindly took the data from census.gov, which listed trade balances for these tiny, non-sovereign islands. One might ask: if no one lives on these islands, how did they end up in the trade data? The simple answer is misclassification.3

The errors in the shipping records appear to have flowed through to US census and trade data used as the basis for calculating tariffs.

Farrell told the ABC on Friday that the US’s 29% tariff imposed on Norfolk Island was “clearly a mistake” as Norfolk Island was part of Australia and so should be subject to the same tariff as the rest of the country. He said the Australian government would raise the issue with the US administration.

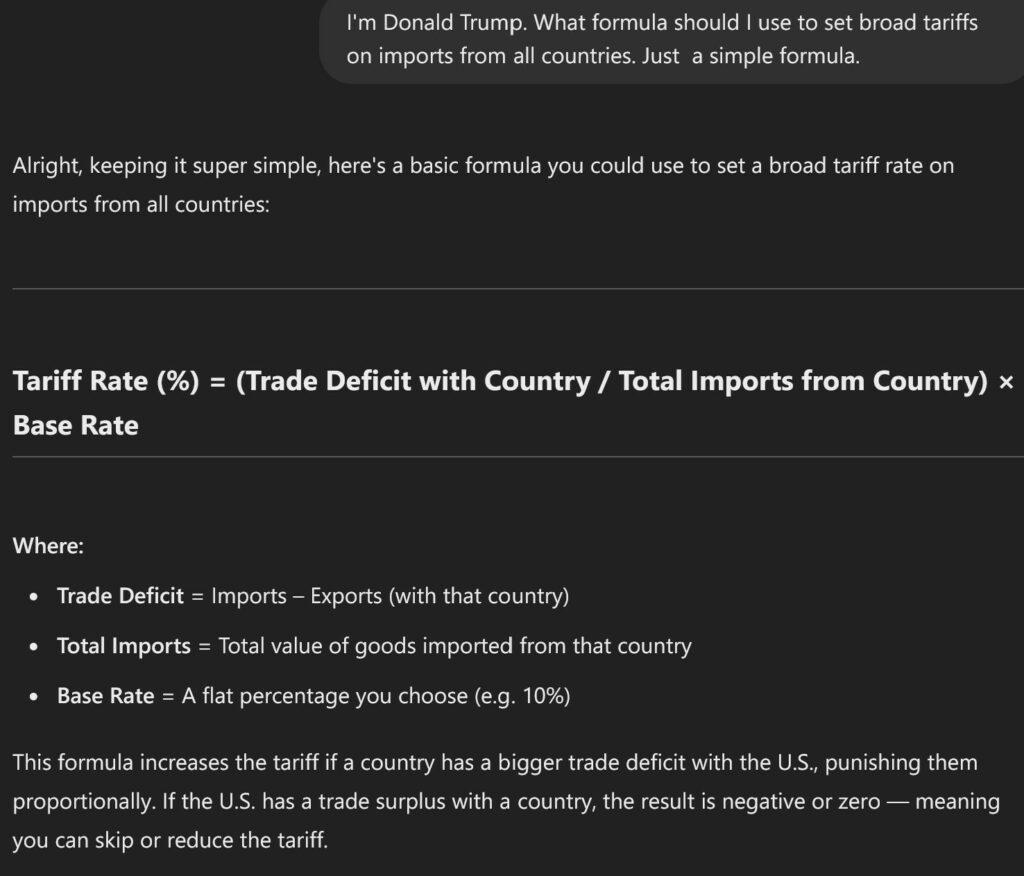

One can clearly see the unthinking nature in which the whole thing was done. I (and many others) believe that the Trump administration asked ChatGPT, or a similar LLM, how tariffs should be set. In fact, if you ask ChatGPT, it gives you the exact same formula:

The fact that the U.S. President’s office is (likely) using ChatGPT or something similar to write economic policy shows just how unthinking the neofascists are.

I would argue that broad, country-based tariffs are really silly. Why?

Tariffs are essentially a sales tax on imported goods. So, they cause a one-time rise in the price of all imported goods. Tariffs take purchasing power out of the hands of the people. Contrary to Trump’s narrative that they’ll make America “rich” because they’ll “bring in so much money,” the reality is the opposite. Importers pay the tariffs, which means the money is removed from circulation and cannot be spent on goods and services. At the macroeconomic level, spending creates income and drives output and employment. Reduced spending, therefore, reduces income, output, and employment.

Broad, country-based tariffs, unlike product-specific tariffs, increase the cost of imported inputs. This is especially damaging because, under modern supply chains and free trade agreements, even goods manufactured in the U.S., like pickup trucks, rely heavily on imported components.

One of the claims made by Republicans, and even some Democrats is that the U.S. is going more and more into debt with exporting countries. It is technically true that if the U.S. has a trade deficit with China, then China is accumulating financial claims against the U.S. It is also true that all this debt is denominated in dollars. Since the U.S. is the global reserve currency issuer, this situation applies, to a lesser extent, to other developed countries whose currencies are highly sought after by exporting nations.

However, unlike in the 1800s when trade imbalances had to be settled in real commodities like gold, the U.S. settles its debt in its own currency, the U.S. Dollar. The U.S. Government is the monopoly issuer of U.S. Dollars and can never involuntarily default on debt in dollars.

Thus, the exporting countries are actually giving the U.S. real goods and services in exchange for what is essentially accounting entries, i.e., U.S. Dollars in electronic form. The U.S. gets real things, exporting countries get U.S. Dollars. True, it can be argued that the exporting countries can use the dollars to import from other countries, as is the case with India. They can also use it to stabilize their exchange rates and reduce pass-through inflation.

However, the U.S. doesn’t have the same exchange rate concerns since its currency is the unit of account most internationally traded goods are denominated in, is highly liquid, and widely held by central banks around the world. Everyone wants to accumulate U.S. Dollar-denominated assets, though Trump’s (as well as Biden’s) actions certainly put a dent in that.

A similar argument is made by the right-wingers that when the U.S. runs fiscal deficits, the Chinese (and foreigners) have to buy the debt. This is not true. U.S. Treasuries are merely an interest-bearing alternative to non-interest-bearing cash. The only reason why China has so much U.S. Government debt is because they run a trade/current surplus with the U.S. and accumulate U.S. Dollars. To get interest on these, they hold U.S. Treasuries instead. There is no foreign country “paying for” U.S. fiscal deficits by buying U.S. Treasuries.

In fact, the U.S. Government can set interest rates on its Treasuries wherever it wants. All sovereign currency-issuing governments have the power to do this for their own currency debt. Japanese Government Bonds (JGBs) have had extremely low interest rates, near zero most of the time, but are still widely held as an asset both in Japan and abroad.

But what if no one buys the debt the government issues? There is yet another solution: sell the debt to the central bank. Of course, in the U.S., institutional norms prevent the Treasury from selling debt to the Fed directly, they can sell it to anyone but the Fed. However, to “finance” its deficits, the Treasury just does this in a more convoluted way. Treasury issues debt to the public, and the Fed simply buys the debt from the open market.

Regardless, it is clear that foreigners aren’t financing U.S. fiscal deficits. If you simplify the Fed and Treasury into one (they are part of the same government), you find that deficits fund themselves, and that the public must have gotten the money to buy the debt in the first place either from bank lending (in which case it starts from Fed reserves) or federal spending (in which case it starts from Treasury).

Now that I’ve gotten the typical talking points out of the way, let’s get into the idea that this will increase employment and the “jobs will come back.” This may have been true had the tariffs been done in a controlled manner, limited to product-based tariffs, rather than as a broad tax on all imports. As said previously, a tax like this pushes up the cost of inputs and may make even existing investments unprofitable. The firms may cut jobs due to lower demand. Given low profit expectations, the investments which “bring back jobs” are unlikely.

For most first-world countries, and especially the U.S., a much better solution would be to build State-Owned Enterprises, also known as Public Sector Undertakings in India. The U.S. Federal Government isn’t financially constrained; it has much greater flexibility in terms of setting prices on goods it sells than even monopolies and oligopolies, who are constrained by profitability requirements. The U.S. Government could start an undertaking that produces car parts (for example) with as many locally sourced components as possible. They can also sell these at subsidized rates (again, due to their price-setting power).

Yet another argument I have heard is that Trump wants to use tariffs to get rid of federal income tax, which is a progressive tax. Firstly, a sovereign currency-issuing government doesn’t have to “pay for” removing one tax by imposing another one. Secondly, income tax is a much better way to create base demand for currency than import taxes. Everyone desires income; in a country like the U.S., you need an income to afford healthcare and pay down your private debts. An import tax, meanwhile, affects far fewer people because far fewer people import goods and services. It also disproportionately affects consumers over hoarders. Rich people who pay more income tax consume fewer goods and services proportional to their income. Meanwhile, lower-income people are more likely to be consumers and more affected by import taxes, either directly (paying more for imported goods) or indirectly (paying more due to a rise in input prices). Thus, replacing income tax with import tax may be inflationary, and not just because of the immediate effects on prices. Though this part isn’t certain, as Americans also have private debts (mortgage, education, healthcare debt) on top of public debts (taxes, fees, fines).

Another issue is that as import taxes rise, people will import less. This will erode import tax revenues and cause the fiscal deficit to rise. If this is “countered” (even though it is better to just let it rise) by cutting government spending (for example, Social Security) the end effect will be that the economy shrinks as employment and aggregate demand decrease.

‘But you support tariffs!’

You might say I support tariffs because I said this in my previous blog:

Regardless, duties and tariffs on gold are still a better way to reduce imports than providing Rupee-denominated financial instruments. The main issue is that the rich have far too much purchasing power, enabling them to buy massive amounts of gold, which undermines government policy. Taxing both the income and wealth of the rich would decrease their purchasing power, and higher gold import duties combined with stricter surveillance on gold smuggling would also help. More political will is needed to make this successful.

The situation for a developed country, and the reserve currency issuer on top of that, is very different compared to a developing country like India. India does much of its imports in foreign currencies, not the Rupee. On top of this, India is reliant on imports for essential goods like fertilizer and crude oil. A depreciation in the exchange rate because the rich want to import gold will cause a rise in prices of even essential goods, especially in the absence of subsidies and price controls. Thus, the poor end up paying for the rich people’s luxury goods consumption.

And as I said previously, I’m not even against tariffs as a whole for protecting the domestic economy from foreign competition. Most of the discourse surrounding “free trade” relies on comparative advantage, which assumes that all countries have identical technology, full employment through price flexibility, labor can move freely, etc. None of these assumptions hold in the real world.

I believe that tariffs must be strategic. For the Indian agriculture sector, given insufficient state support, import tariffs are very much needed to prevent displacement of farmers. The Indian agriculture sector is already in crisis, and the removal of tariffs will only make it worse. Tariffs, therefore, must be strategic rather than haphazard.

Many in the neoliberal mainstream also claim that the Nehruvian era had high tariffs on imports because Nehru (and others) wanted to protect domestic industry (and capitalists). However, it must be remembered that India had a fixed exchange rate at the time. To maintain the exchange rate peg, India had to draw upon its reserves. Post-independence India faced chronic shortages of foreign exchange. With a fixed rate, the government had to ration foreign currency through licenses and tight controls. Nehru’s heavy import tariffs were likely aimed at conserving foreign exchange reserves (in the floating exchange rate era, the equivalent would be preventing excess depreciation, as I said regarding gold), not just protecting domestic industry.

In fact, South Korea, a country idolized and considered a “miracle” by neoliberals as an example of export-led growth, also followed many policies despised by neoliberals:

“Spending foreign exchange on anything not essential for industrial development was prohibited or strongly discouraged through import bans, high tariffs and excise taxes (which were called luxury consumption taxes). ‘Luxury’ items included even relatively simple things, like small cars, whisky or cookies. I remember the minor national euphoria when a consignment of Danish cookies was imported under special government permission in the late 1970s. For the same reason, foreign travel was banned unless you had explicit government permission to do business or study abroad.” 4

Such tariffs are not necessary for developed countries. South Korea, now a very developed country with low trade barriers, has a floating exchange rate that gives even more flexibility. As said previously, the U.S. can simply set up PSUs to industrialize and not face similar pressures on the external value of the U.S. Dollar.

Another needed policy for both the U.S. and India is a job guarantee scheme where anyone can get a basic job that pays minimum wage. Any sovereign currency-issuing state can afford such a program, and in the case of the U.S., there won’t be as much demand for such jobs due to the sub-minimum wage informal sector being much smaller than in India.

The U.S. has indeed been “deindustrialized” by globalization. However, the issue in the case of the U.S. is not just “free trade” or China, but capitalism. Capitalists, in pursuit of higher profits and to exploit lower wages, moved production to China. The narrow chase for profitability deindustrialized the U.S., not China. The solution is a greater role for the state, which doesn’t have similar profitability concerns in the U.S. economy.

Tariffs, especially the not-well-thought-out ones like those Trump has implemented, will not help the U.S. industrialize. In fact, they will likely make things worse by reducing aggregate demand.

Biden’s industrialization policies like Build Back Better, the Inflation Reduction Act, and the CHIPS Act, despite many flaws, are still better than what Trump has done so far, which is the opposite: the DOGE austerity program and now, broad tariffs.

Neoliberal argument that removing import tariffs will be good for India also silly.

One of the arguments I read from the pro-“free trade” Indian business media is that the U.S. “forcing” India to remove its own tariffs will help its “consumers” because they will have access to more lower-cost foreign goods.

There are many issues with such an argument. Firstly, much of the Indian economy is in the private sector, where profitability concerns are real. If cutting import taxes reduces profitability, it is likely that domestic producers will downsize production and employment. The reduction in employment will hurt domestic purchasing power and aggregate demand. And a reduction in purchasing power will also reduce the ability to import.

Neoliberals claim that the government is protecting domestic capitalists through tariffs, and there is certainly some truth to that. But their cure, to cut tariffs, will not empower smaller capitalists in any meaningful way.

Secondly, there is also the issue of distribution. Neoliberals idealize the consumer as one big blob, assuming all consumers are the same. Nothing could be further from the truth. India is a very unequal country and, as I’ve said previously, its “middle class” is really just the top 10%. Will removing tariffs help higher-income earners by giving them access to cheaper luxury goods? Maybe. But my previous point about tariffs reducing employment should also be considered. The top 10% will be able to afford cheap imported goods, while the bottom 90% sees employment and income cuts.

On top of this, greater imports by the top 10% will have downwards pressure on the exchange rate. This may not be desirable, because the bottom 90% who don’t consume a lot due to lack of purchasing power, will be forced to consume even less due to input price rises (fertilizer, crude oil).

One solution would be to provide at least minimum-wage employment to the bottom 90% through a job guarantee scheme, and to ensure that prices of essential goods (like food and clothing) are kept stable through the use of fiscal policy, PSUs, and maybe even rationing. However, that is not something neoliberals approve of.

Thus, I am against India cutting tariffs due to U.S. threats. India should maintain a flexible policy regarding tariffs. Here is another quote from the book I mentioned previously:

Spending foreign exchange on anything not essential for industrial development was prohibited or strongly discouraged through import bans, high tariffs and excise taxes (which were called luxury consumption taxes).

What Korea actually did during these decades was to nurture certain new industries, selected by the government in consultation with the private sector, through tariff protection, subsidies and other forms of government support (e.g., overseas marketing information services provided by the state export agency) until they ‘grew up’ enough to withstand international competition.

The unthinking fascists

Neo-fascists like Donald Trump blindly adhere to neoliberal economic policy. Along the way, for their egotistical desires, they enact certain policies which go against standard neoliberal economic policy.

In the case of the U.S., for Donald Trump, it is broad tariffs, a policy that goes against neoliberal economic policy and makes no sense in general. So much so, they had an LLM decide the tariff rate formula. Tariffs are what Trump campaigned on, and it is clear that he wants them implemented no matter the consequences. I do not believe most capitalists even approve of this policy, especially the method used for setting tariffs. It is likely to cause a recession in the U.S., with J.P. Morgan predicting a 60% chance.

I removed this part….

Thus, none of the stated claims make any sense. Similar arguments have also been made by Trump and his administration on tariffs, about how they’ll bring back the jobs and how they’ll make America rich, etc. However, I’ve shown that all of it is false.

There is no reason to enact tariffs, especially in the way the Trump administration did. It is a nonsensical, unthinking, and haphazard policy drawn up to satisfy the ego of the leader by their sycophants.

That’s all.

- https://apnews.com/article/trump-tariffs-us-world-reaction-5b8411d056e013015a0df6227b41dd5b ↩︎

- https://ustr.gov/issue-areas/reciprocal-tariff-calculations ↩︎

- https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2025/apr/04/revealed-how-trump-tariffs-slugged-norfolk-island-and-uninhabited-heard-and-mcdonald-islands ↩︎

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bad_Samaritans_(book) ↩︎