In mid-1991, India’s foreign-exchange reserves had plunged to roughly US $1 billion, barely enough to cover two weeks of imports under its fixed exchange rate regime. As the RBI drew down scarce dollars to defend the parity amid Gulf War oil shocks, rising global interest rates, and falling remittances, external credit lines dried up and NRI deposits were withdrawn.

One of the major reasons for India’s balance of payments crisis in 1991 was the rigid exchange rate regime it had adopted. In the 1980s, with trade liberalisation, India experienced a significant rise in imports of ‘white’ goods from abroad, such as refrigerators, TVs, and washing machines, by higher-income earners.

The issue is that with fixed exchange rate, the Government of India had to pay for these imports. Why? Because, any excess supply of Rupees in the foreign exchange market due to such imports will put downward pressure on the exchange rate and cause it to move beyond the target. This means the RBI had to use the limited foreign exchange reserves it had to pay the import bill. It also presented another problem, if the RBI was low on reserves due to a trade deficit, it had to borrow foreign currency from international markets whether it’s NRI Deposits, IMF or other international lenders. NRI Deposits are liabilities of India and has to be settled in foreign currency. This meant the country cannot use its currency issuing capacity to pay back the debt and had to try to somehow export enough or borrow even more.

The fixed (more or less) exchange rate also reduced India’s trade competitiveness which further promoted imports and reduced exports. There were several other issues I will come to later.

The shocks India and the global economy experienced in the 1980s, like the Gulf War which increased oil prices, reduced remittances, as well as the high interest rates in the U.S., further put pressure on India’s external balance. Eventually, India’s dwindling foreign exchange reserves and its inability to obtain foreign currency compelled it to go to the IMF. The dissolution of the USSR and the Eastern Bloc meant India had nowhere to turn to for financing essential imports. It was also the era of neoliberalism, where neoclassical economic policies dominated among the elite. For them, there was no alternative to neoliberalism. There was a growing consensus among the bureaucracy, economists, and sections of the various political parties that liberalisation was necessary.

Many in the neoliberal circles blame ‘License Raj’, ‘Fiscal populism’, ‘Twin deficits’, ‘Loss-making PSUs’, etc. However, rarely is attention ever focused on the actual issue causing foreign currency indebtedness, i.e. a fixed or tightly managed exchange rate. Had India floated the rupee in the 1980s or even the 1970s, it would not have faced the issues it did. It could have even floated in 1991 without getting ‘assistance’ from the IMF, but of course, that would have caused a major economic shock as prices adjusted. I’m not saying India wouldn’t or shouldn’t have liberalised, that is a political question, but that it wouldn’t have faced such a severe crisis as it did had it floated the rupee.

Much of the reasoning neoliberals point to falls apart on scrutiny.

- License Raj: It was claimed that the License Raj created a situation where well-connected insiders got preferential access, and to some extent that is true. India always had a significant private sector, and where there is a private sector, there is corruption. However, most ignore the fact that the License Raj’s main function wasn’t just protectionist ‘red tape’, as neoliberals claim, but foreign exchange reserves conservation. Since pre-1991 India had faced chronic foreign exchange shortages, it was thought that restricting companies using licences and quotas would also reduce the use of foreign exchange, and to some extent that was probably true. So, clearly, the License Raj wasn’t to blame for the 1991 crisis.

- Loss Making PSUs: Another very common claim is that ‘loss’-making PSUs made the fiscal deficits worse and caused the 1991 crisis. This does not make much sense either, since the Indian PSUs ran deficits in rupees, not foreign currency. While one can argue that the deficits from such PSUs fed into greater imports (whether it was salaries or inputs), after all, government workers were relatively well off compared to the rest of the population, just as is the case now, the actual problem was still the fixed exchange rate. In a floating exchange rate regime, such imports would have resulted in a depreciation and not in a loss of reserves. Again, the real issue was the fixed exchange rate, not the PSUs running deficits. The ‘loss-making’ narrative fits the neoliberal agenda of privatisation, but that does not make it right.

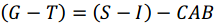

- Fiscal Deficits: Yet another reason given by the neoliberals for the 1991 crisis is the fiscal profligacy of the government at the time. However, there are many problems with this argument. Firstly, as a matter of accounting:

Where (G–T) is government spending minus taxation, the fiscal balance, almost always in deficit; (S–I), saving minus investment, which is the private sector balance, almost always in surplus for the economy as a whole; and CAB is the current account balance, which includes the trade balance, net transfers, and net income from abroad, almost always in deficit for India.

This shows us that the high fiscal deficits in the 1980s were actually stimulating aggregate demand and keeping economic growth higher. Had the Indian government attempted extreme austerity, the economy would have gone into a recession, exports would have collapsed, and the 1991 crisis would have happened much earlier.

The issue was always the fixed exchange rate, which forced the government to be indebted in foreign currencies and dependent on external financing of its current account deficits. In a floating exchange rate system, the government simply does not have to be indebted in foreign currency unless it seeks to target a particular exchange rate and cannot obtain the foreign currency through trade or local currency assets bought by foreigners. Even in such a case, it is unwise to go for a foreign currency loan as it opens up the country to similar risks.

The 1980s boom, where India recorded high 7–8% growth rates, delayed the inevitable balance of payments crisis. Of course, the boom was not sustainable, as the imports were financed by foreign currency debt. However, it did improve industrial capacity and productivity and maintained some stability. As for the increased import intensity, it could have been avoided had India floated the rupee, as it would have forced manufacturing to use more domestic resources.

With a fixed exchange rate, the Indian private sector had no incentive to build local supply chains, as they could source the same from abroad with the state indirectly footing the bill, all while the neoliberals pointed fingers at twin deficits or loss-making PSUs.

- Twin Deficits: Neoliberals love to point out that India had a large fiscal deficit (G–T) and a large current account deficit (CAB) in the 1980s and then imply that ‘overspending’ by the state caused this current account deficit.

The sectoral balance identity from before shows that the fiscal deficit merely accommodated the private sector demand to net save. India’s budget was entirely rupee-denominated, so as long as there is demand for rupees domestically and it remains the money of account, there will be demand for sovereign rupee debt as it is the only true risk-free asset.

The real constraint for India after its independence and until the 1990s was the external balance, which under a fixed exchange rate regime had to be financed by increasing amounts of foreign currency debt. The unwillingness of the government to devalue the rupee more often, fearing passthrough inflation and political blowback among urban consumers and businesses, made matters worse.

Why private sector access to fixed/rigid exchange set by the Government can become unsustainable

Many on the left argue that India’s fixed exchange rate in the 1970s and 1980s was at least somewhat of a good thing, as it kept the exchange rate and hence local prices stable for the working class. In reality, rigid exchange rates cause indebtedness in foreign currencies when the country is unable to export and earn enough reserves to maintain the peg. Secondly, fixed exchange rates create incentives for fraud and corruption, especially when the private sector is involved, whether it is smuggling, lying on documents in outward remittance forms, misinvoicing trade or straight-up ghost imports.

When the private sector is allowed access to the fixed exchange rate, the government has to satisfy their desire for foreign exchange. This can only be prevented by not allowing the currency to be convertible at the fixed exchange rate for most people or by continuously updating quotas for foreign exchange at the fixed exchange rate so as to maintain reserves. The latter is not a good option, as it creates major uncertainty for people wanting to trade foreign exchange.

In my previous blog ‘Indian Government has limited control over the Rupee exchange rate’, I explained this: foreign exchange is a limited resource, and exports are exogenous. India does not have significant control over global demand for its goods. In it, I said that the RBI could burn reserves and try propping up the exchange rate at its own discretion. With a fixed exchange rate, however, that rate is non-discretionary and any failure to provide that rate, either by devaluation, floating or through tightening capital controls, is akin to a default. You are saying you would convert foreign exchange at a fixed price and defaulting on that promise.

Many on the left think that since the Soviet Union and the Eastern Bloc had fixed exchange rates, it was good and also applicable to capitalist countries. In reality, the Soviet Union never had a fixed exchange rate system. The de facto rate available to the vast majority of private individuals was a floating rate, through the black market. This is not a criticism of the system either, as this kind of black market does not impinge on the state’s reserves in a significant way, since these trades do not involve central bank reserves and arise merely from demand mismatches. Officially, the Soviet rouble was a non-convertible currency. The Soviet government never provided any exchange rate to private individuals. For international trade and accounting, it used a variety of fixed exchange rates at its own discretion. This meant the government could use the reserves as it saw fit for trade and transfers. It was not at the mercy of private demand for foreign exchange. This is not a criticism of the Soviet or socialist system, but just an observation.

Thus, my support for floating exchange rates does not come from some belief that markets are better. It comes from an understanding of how sovereign governments, whether capitalist or socialist, get the most fiscal space to mobilise domestic resources under a floating exchange rate regime. The Soviet Union shows us that full employment can be achieved and domestic resources utilised effectively if the currency is not convertible at a fixed exchange rate.

Greece as an example

Greece is probably the best example of what a fixed exchange rate can do when taken to the extreme. Greece gave up its monetary sovereignty by adopting the Euro as its currency on 1st January 2001. Many economists, particularly the post-Keynesians and MMTers, saw a disaster incoming. By adopting a foreign currency, the Greek government lost many of its powers, like the power to devalue or float their own currency, adopt independent monetary policy, and its debt was no longer risk-free as it no longer issued its own currency. This meant that if tax revenues dwindled due to an economic shock, the government would be forced to borrow from the market. Unlike sovereign currency spending, like in India, Greece had to borrow in order to spend in excess of tax revenue.

In late 2009, Greece and many other Eurozone countries plunged into a ‘sovereign’ debt crisis. The name is misleading since the debt was not really sovereign. But regardless, Eurozone countries which had adopted restrictive fiscal policy, like Portugal, Italy, Ireland, Greece and Spain (PIIGS), under the Maastricht Criteria, saw their fiscal deficits blow up due to a collapse in tax revenue and a natural increase in spending due to automatic stabilisers such as unemployment cheques and welfare. The rise in spending on automatic stabilisers was not discretionary and was merely the result of the 2008 Global Financial Crisis causing economic hardship among the people. It only replaced some of the private income that was being lost and cannot be considered fiscal profligacy. Of course, many countries did implement discretionary fiscal policy by rescuing banks, but these were stabilising, not expansionary, policies. Not doing so would only have worsened the situation and cut tax revenues further.

When the bond markets realised that Greece might not be able to pay its debt, they started demanding more and more interest. At the extreme, it might not have found a borrower regardless of the interest rate due to the debt burden it faced. Bond yields rose higher and higher until the European Central Bank, the issuer of the Euro, stepped in and decided to be lender of last resort in 2012. Soon after, yields on Greek government debt dropped from nearly 28% in June 2012 to 11% in January 2013. Since then, Greece and other Eurozone countries have not faced a debt crisis. The ECB has always bought member countries’ debt to keep yields stabilised. However, this also means the ECB can coerce member countries into doing what it wants. For example, if a Eurozone country wants to increase healthcare spending from 3% of GDP to 5% of GDP, the ECB can threaten to stop buying the country’s debt. Thus, these countries still lack complete sovereignty.

This rescue was not without its costs. The Troika, consisting of the EC, ECB and the IMF, imposed extreme ‘adjustment’ programmes on these countries with sharp cuts in spending and by forcing so-called ‘internal devaluation’ where wages of the workers are cut to make the country’s goods and services more competitive, which collapses domestic aggregate demand. Greek GDP still is not anywhere close to the peak it hit in 2008 and likely will not be for decades to come. Hundreds of thousands of Greeks migrated abroad due to high unemployment and low income at home. It was a social and economic disaster.

What if Greece had its own floating currency? Its private sector would not have become so indebted to foreign banks in other Eurozone countries. It would have seen a sharp depreciation in the exchange rate, which would have caused a one-off reduction in purchasing power. However, it would have also increased external competitiveness without any ‘internal devaluation’. This is especially important for a country like Greece, which attracts hundreds of thousands of tourists. It could have also imposed temporary capital controls to slow down and limit the depreciation. There would have been a decline in growth and a recession, as was the case in every capitalist country. However, the country would have recovered quicker because the sovereign state would have been able to do counter-cyclical economic policy. It would not have faced the cruel adjustment programmes of the Troika either. Growth would have returned in a few years instead of what happened that is decades of stagnation.

What does this have to do with India? The fixed exchange rate India adopted pre-1991 made it vulnerable to economic shocks and increased foreign currency indebtedness. Unlike Greece, India never faced any issues with its own currency. Indian sovereign bonds always had high demand and always will as long as the Indian state exists. Had India floated early, it would have still faced a sharp depreciation in the rupee exchange rate during the Gulf War, essentials would have become more expensive. But the government would not have gotten into foreign currency debt just for the rich to import luxury goods and obtain foreign exchange for cheap. It could have used the foreign exchange it obtained where it mattered that is on imports of essential commodities like fuel, fertiliser, medicines etc., distributed directly using the public sector so as to prevent the private sector from committing fraud, as has happened in many countries, e.g. Venezuela with CADIVI.

Comparison between 1991 India and 2013 India

Now that we have seen how India’s fixed exchange rate led to the 1991 Balance of Payments crisis, let us compare what happened in 1991 versus what happened in 2013.

In 2013, India faced a sharp depreciation in the exchange rate of the rupee during the ‘taper tantrum’ crisis, as speculation about U.S. interest rate hikes triggered capital outflows from nearly all developing countries. India’s current account deficit reached 4.8% of GDP, yet there was no crisis like what happened in 1991.

Why? The major difference was the exchange rate regime, as well as the way in which the current account deficit was financed.

India in 2013 had a managed floating exchange rate regime. With this, the RBI only occasionally intervenes in the foreign exchange markets to smooth out volatility, but not rigidly targeting any particular exchange rate. The RBI does target exchange rates based on how it thinks markets will react if the exchange rate goes beyond the target. It also intervenes to prevent excess appreciation in the exchange rate due to capital inflows, as appreciation can undermine trade competitiveness. This is a large part of why the RBI’s foreign exchange reserves ballooned in the 2000s, as it purchased foreign currencies in the foreign exchange market to prevent excess appreciation. Unlike under a fixed exchange rate, these interventions are discretionary, not obligatory. The RBI is no longer bound to defend any particular level of the exchange rate. The mainstream claim that the RBI accumulated these reserves as an ‘insurance policy’ is not completely true.

The RBI simply let the floating exchange rate depreciate around 18%. This caused a rise in inflation due to exchange rate passthrough and had important effects on the socio-political situation at the time. However, India did not experience a 1991-like Balance of Payments crisis simply because there was no peg to defend.

The second aspect is the nature of current account deficits. In mainstream news, and even among many left-leaning commentators, trade and current account deficits are demonised and seen as a ‘bad’. This is likely in part due to India’s experience with the 1991 crisis. However, the nature of the current account deficit then versus now is completely different.

In the 1980s, due to the fixed exchange rate, the Indian government was forced to become more and more indebted in foreign currencies. In the present day, that is not the case. India’s current account deficits are financed by purchases of local currency financial assets by foreigners. As the sovereign issuer of the rupee, the local currency, the Indian government can always finance its current account deficit. This is why, despite a larger current-account-to-GDP ratio in 2012 than in 1991, India did not face a similar or worse crisis.

In present-day India, current account deficits do not tell you much beyond the willingness of the rest of the world to accumulate financial claims against India. These financial claims are mainly in rupees and can always be financed without issues. Thus, current and trade deficits are not very useful in determining the economic situation in the country.

In 2013, India’s current account deficit fell from 4.8% to 1.7%. This was because exports slightly grew and imports shrank significantly due to the depreciation of the exchange rate. While the latter is unfortunate, it was only the result of the external shock, the aforementioned ‘taper tantrum’, over which India had very little control.

On capital controls

While I do favour a floating exchange rate, it is not because of market fundamentalism but because of the inherent instability and problems with fixed exchange rates. I am not opposed to capital controls, but their use and extent should depend on the prevailing material conditions in the country.

While it is true that allowing foreigners to purchase financial assets in India has enabled it to run the ‘better kind’ of current account deficits, these purchases have also made the country vulnerable to global financial flows. Sudden swings in exchange rates driven by such ‘hot money flows’ can be very damaging to the domestic economy, as was seen in 2013 and 2022.

India’s capital account is not completely open; there are sectors where foreign investments are limited by law. While the Indian rupee exchange rate does not face any extreme threats for now, it is only prudent to tighten capital controls if the exchange rate starts depreciating too sharply.

This does not mean India should shut itself off from foreign capital. Long-term, stable investments in technology and manufacturing can help improve productivity and create quality employment while improving the stability of the exchange rate. Short- and medium-term flows, while bringing certain benefits for certain parts of society, e.g. importers when the exchange rate is stable or appreciating, can be damaging and cause economic shocks when they stop and reverse suddenly. Regardless, not even such flows are as damaging as increasing foreign currency indebtedness for defending a fixed exchange rate. The comparison between 1991 and 2013 proves this.

But what about rising prices due to depreciation?

While India did not face the same crisis as 1991 in 2013, the sharp rise in inflation due to exchange rate passthrough had significant effects on the political and social situation in the country. The high inflation eroded real purchasing power. While the top 10% cut back on non-essential imports, the bottom 50% faced much more severe distress. Farmers saw input costs such as fertilisers rise, petrol and diesel prices rose, which caused transportation costs to rise, and since transportation is used for pretty much all goods, even the prices of essential goods like food and other groceries increased significantly.

What could have been done to ease and possibly spread out the pain? One solution would be for the RBI to sell large amounts of foreign exchange reserves in the foreign exchange market so as to stabilise and ‘glide’ the exchange rate slower, maybe even keep it stabilised. However, there are issues with such an approach:

- It makes the exchange rate resemble a peg, whether it is a crawl or a ‘stabilised arrangement’. This increases speculation on the rupee, as speculators try to break the peg. Capital controls limit this somewhat, but it is still a cause for concern. Reserves are lost to speculators. The most egregious case of this was the 1992 Sterling Crisis, where the central bank, the Bank of England, tried defending the exchange rate by raising interest rates and burning billions of dollars of foreign exchange reserves. The fixed exchange rate, combined with open capital flows, caused the peg to break, and speculators like George Soros made billions from it. Even without speculators, it helps foreign investors cash out in foreign currency before the eventual depreciation.

- It promotes external borrowing in the private sector. Businesses can get lower interest loans abroad denominated in foreign currencies, say in the U.S., exchange it for rupees and get what appears to be cheap financing for their needs. However, when the exchange rate depreciates because the RBI sees reserve drain being too high or if it perceives that the peg is misaligned, the rupee financing costs for these businesses increase dramatically. Fortunately, this is not a sovereign issue; if the debt is too high, the businesses go insolvent. This still can have significant effects on output, employment, and financial stability, even if the government is not on the hook.

- It promotes fraud and corruption. In previous paragraphs, I mentioned Venezuela’s CADIVI. CADIVI was established in 2003 by the Venezuelan government as a currency control regime.

It was meant to allocate foreign exchange to Venezuelan importers and individuals at official exchange rates while attempting to prevent capital flight. The multiple exchange rates it offered to the private sector created massive incentives for fraud.

For example, if the government was offering foreign exchange for medicine at $1 = 4 VES, fraudsters would create a shell company, provide false documentation, not import anything, and sell the foreign exchange obtained in the black market for more local currency.

Thus, the government’s foreign exchange reserves were drained to make fraudsters rich. India also had a similar issue pre-1991 and still does to a lesser extent, where individuals and businesses use fake invoices or overvalued imports to get foreign exchange at the official rate and sell it in the black market at a higher rate. Though, if the RBI does not intervene in the official exchange rate, this is not a drain on reserves.

- It subsidises everything. This is the key issue with stabilising widely available exchange rates. Even if it is assumed that there is no fraud, the RBI has sufficient reserves, and the capital controls are perfectly effective, the Indian rupee is convertible at the official rate. This means every import, from crude oil and food to luxury bags, watches, and gold bullion, is imported at this exchange rate. The RBI ends up indirectly subsidising luxury imports, vacations abroad, purchases of assets abroad, etc. This is clearly a waste of foreign exchange reserves.

These are the reasons why I have always been critical of the ‘stabilised arrangement’ of certain currencies between late 2022 and late 2024. It was unsustainable in the long term, wasted public resources, promoted private indebtedness in foreign currencies, and promoted fraud and corruption. Regardless, with the Trump shock, the dollar has been having issues, so it will be some time before such interventions resume, if they even do.

Support essential commodity prices instead of the exchange rate

My view is that developing countries like India should focus on stabilising and supporting essential commodity prices instead of exchange rates. This ensures that everyone, and more importantly, lower-income people, are not affected too badly. The better off can cut down on imports of non-essential goods.

What are essential goods? They can include goods like petrol, diesel, LPG, wheat, rice, fertilisers, medicines, etc. Goods we need to survive, as well as those that form the building blocks of the supply chain.

Of course, the specific goods to be supported depend on demand and the ability of the country to produce them. For example, India may not need to support the import of wheat as it produces significant amounts of it, but may need to support inputs used for it, such as fertilisers, seeds, farming equipment (maybe), and petrol. India also has refining capacity, so it can import crude oil instead of petrol directly, whichever is in the best interest.

I might go into more detail on this in the future, but what I think would be the best idea is a state import agency, maybe something called the ‘Essential Imports Board’, established by law, which manages imports of just essential goods listed in a schedule so as to prevent creep. Instead of the RBI intervening and selling foreign exchange, this agency will have access to RBI foreign exchange, PSU foreign exchange reserves, as well as a direct grant line from the RBI. The grant line must be capped to a certain percentage of rolling exports (or similar) for the last six months so as to prevent runaway depreciation of the exchange rate.

To reduce corruption and incentives for arbitrage, only PSUs will be able to be contracted by this agency. This ensures a proper audit trail and cuts away much of the fake invoicing issues associated with CADIVI and other state import agencies in other countries. Transparency is a must for this agency, as it will be making monetary-fiscal decisions and has a limited grant line from the RBI. A public dashboard with all the information, perhaps?

The point of this agency is not to keep prices low forever, but to provide a glide path for prices of essential goods. So, for example, if crude oil prices go up from $50 to $100 a barrel, the agency will use the foreign exchange reserves and grant line (if needed) to make the prices crawl up slowly over time. Depending on the reserve drain, the agency will be able to speed up or slow down the crawl rate.

This ensures that:

- Essential goods prices only increase in a controlled manner and the economic shock is flattened out over months.

- Foreign exchange purchases do not lead to runaway depreciation due to hard caps imposed by law.

- Prices for all other imported goods outside the schedule are allowed to float without significant intervention.

- Foreign exchange reserves are not wasted; see the points I made in the previous section.

This is not a promise of heaven or magic. It ensures that available limited resources are most effectively utilised to soften economic shocks coming from the external sector. It does not try to keep prices pegged for an infinite amount of time. It lets all the other prices float as is necessary during an economic shock. This can apply to all economic systems, whether capitalist or socialist.

Conclusion

India’s 1991 Balance of Payments crisis was not inevitable; it was a product of a rigid exchange rate regime that left India exposed to external shocks and dependent on foreign currency debt. While neoliberal narratives blame internal inefficiencies like fiscal deficits, PSUs, or the License Raj, if you look closer, you will see that the real constraint was always the external sector.

Floating the rupee earlier could have prevented the crisis or, at the very least, allowed India to go through economic shocks with less external help. The comparison between 1991 and 2013 highlights my point clearly. India did not face a currency crisis in 2013 not because of the reserves but because it allowed the exchange rate to adjust.

My support for a floating exchange rate does not arise out of market fundamentalism. I acknowledge that floating exchange rates can and do cause volatility, but unlike a fixed exchange rate, they do not force the sovereign to become indebted in foreign currencies.

A sharp depreciation under the floating exchange rate regime creates pressure on the RBI to act. The common way the RBI does so is by aggressively intervening in the foreign exchange market, targeting a particular exchange rate. I pointed out major issues with this approach.

A better approach is to create an institution which, instead of targeting exchange rates, focuses on prices of essential goods like fuel, fertiliser, medicines, etc., with rules to prevent runaway depreciation of the exchange rate. This must be done transparently and with as little interaction with the domestic private sector as possible. The aim is to allow prices of essentials to rise slowly rather than rapidly, especially if the shock is prolonged.

That’s all.