Indian media, both ‘mainstream’ and ‘independent’ outlets, tend to report every change in the trade and current account balances of the country as though it were a warning sign of some impending economic crisis. The narrative is very predictable; if the trade or current deficit widens, it is widely seen as a sign of economic weakness. This, however, ignores what a trade or current deficit actually is.

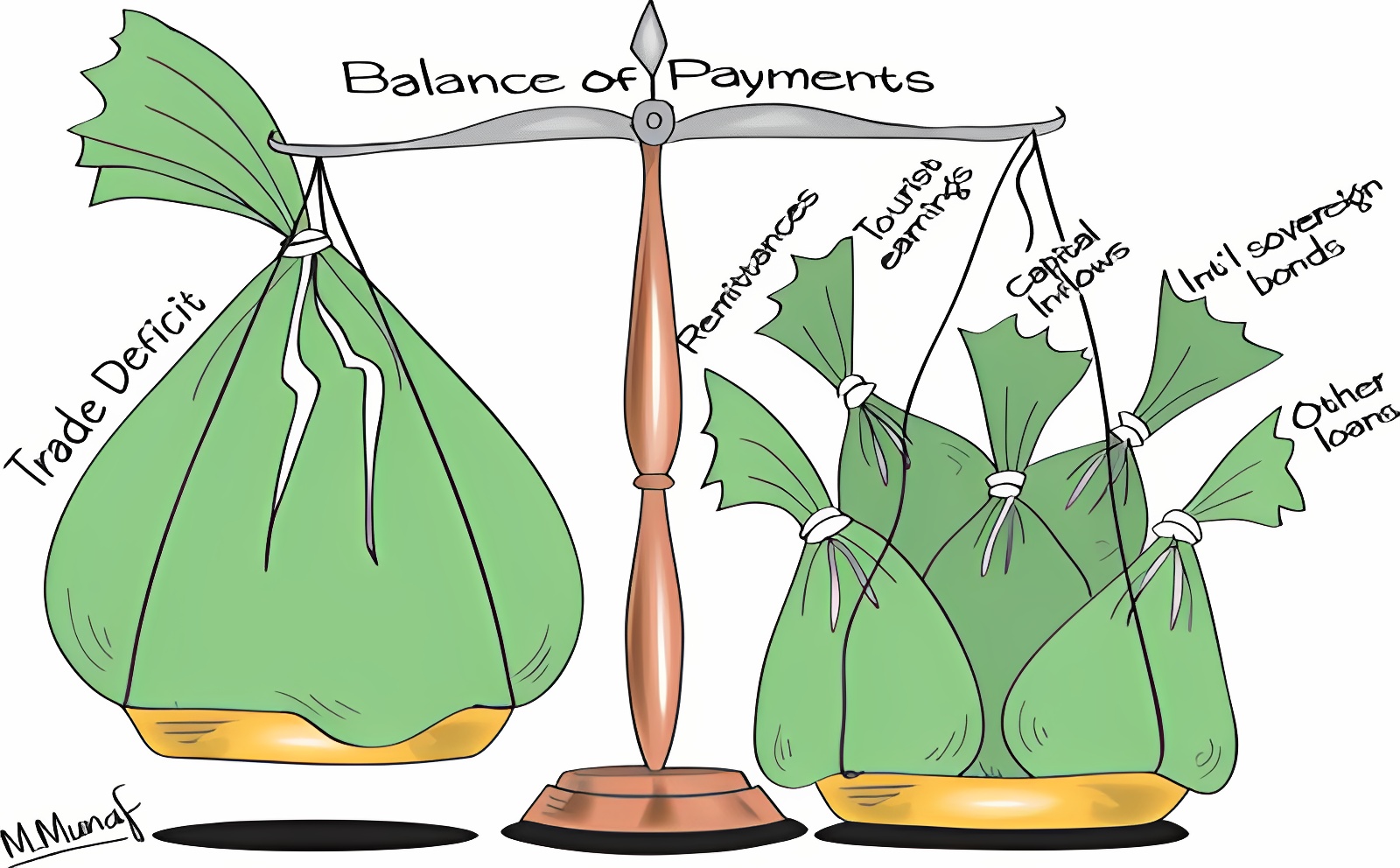

The trade balance is merely the difference between exports and imports of goods and services, i.e. (X – M), where X stands for Export and M stands for Import (the second letters are used since E can also mean Expenditure and I can also mean Investment in many economic equations). So, for a country to be able to import more than it exports, i.e. run trade deficits, the rest of the world must be willing to either:

- Get goods and services for ‘free’ in the form of net transfers. Remittances, for example, are sent by people working abroad to their families; these are, at least from the country’s perspective, an unconditional transfer since they do not increase liabilities. This can also include foreign aid, which typically has political strings attached, but from an economic perspective is an unconditional transfer that does not have to be repaid.

- It can also be in the form of the rest of the world accumulating financial claims against India. For example, foreigners may purchase Indian stocks, bonds, and other financial instruments, or real assets like plant and machinery, land, and real estate. These types of transactions go into the Capital/Financial Account.

These two are examples that go under “Net Transfers” in the Current Account. Another component of the Current Account is “Net Factor Income from Abroad (NFIA).” This includes dividends, interest, and other forms of income that do not increase the country’s liabilities.

Let’s take the equation for the Current Account:

Current Account = Exports – Imports + NFIA + Net Transfers

In my previous blog, I wrote about how the rigid exchange rate regime India had prior to 1991 caused a Current Account Deficit, which forced the country to borrow in foreign currencies to maintain the fixed exchange rate. I also compared the 1991 Balance of Payments Crisis with the 2013 Taper Tantrum and showed that, despite India having a higher Current Account Deficit in 2013 compared to 1991, it did not face any issues with balance of payments.

The key difference, I said, was the exchange rate regime being floating. However, there was another difference: India (both government and private sector) held very little foreign currency debt, relatively speaking. This meant that any depreciation in the exchange rate would not force the government to pay more in local currency to service foreign debt. This is an issue faced by many third world countries and was partly the cause of several hyperinflation episodes throughout history.

Does the U.S. really have a trade deficit with China?

One of the claims put forward by President Trump is that China and other countries with which the U.S. has a trade deficit are ripping the U.S. off. To show you why this is not the case, let’s look at why the U.S. has a trade deficit in the first place. By identity:

Current Account + Capital Account + Financial Account + Errors and Omissions = 0

So, when the U.S. or any other country has a trade deficit (which is a component of the current account), it has an equal and opposite balance in the Capital/Financial Account. So how does this work?

- A Chinese seller is willing to accept U.S. Dollars in exchange for selling their goods or services.

- A U.S. importer provides the Chinese seller with U.S. Dollars by a wire transfer.

- The U.S. importer gets real goods or services, while the Chinese exporter gets the U.S. Dollars in their multi-currency account.

- The Chinese seller has the choice to keep their balance in U.S. Dollars if they have a surplus. In that case, there is no effect on the exchange rate.

- However, if they have to make payments, say to the Chinese government in the form of taxes, they will have to get the U.S. Dollars exchanged for Chinese Yuan. This can be done at the foreign exchange markets. To ensure liquidity, the Chinese Central Bank is there to be the buyer of last resort. They do so by managing the exchange rate.

Notice how the U.S. got real goods in exchange for its currency. It gave financial claims (which, as mentioned previously, go into the capital/financial account) for real goods. The U.S. is, in essence, giving China electronic entries for real goods and services. The U.S. is basically getting something for nothing, just because China and other exporting nations are willing to accept U.S. Dollars. Thus, the desire to save in U.S. Dollars by the rest of the world creates a current account deficit in this case.

The U.S. is not the only country with this privilege; other first world countries like the U.K., Australia, and the EU have the privilege of their currencies being in great demand. Of course, some countries still run a current surplus despite their privilege for various reasons. But the truth is that currencies like the U.S. Dollar, British Pound, Euro, and other first world currencies are demanded disproportionately compared to their economic size. The global appetite for their currencies is what allows them to run consistent current account deficits without facing any significant depreciation in the exchange rate.

Back to the U.S., the Chinese seller gets the U.S. Dollars exchanged for Chinese Yuan. The Chinese government decides to exchange their U.S. Dollars for U.S. Treasuries. Note that this is an asset swap. China is not financing U.S. fiscal deficits; fiscal deficits are a separate thing. China, to get a risk-free interest, decides to buy U.S. Treasuries instead of keeping their foreign exchange reserves in U.S. Dollars without interest.

As the U.S. is the sovereign issuer of U.S. Dollars, it faces no constraint in being able to finance these current account deficits. It does not face the risk of its debt being unserviceable, since it does not have to hand over any foreign currency to pay off its Dollar debt.

But what if China tried dumping U.S. Dollar debt in the foreign exchange market? Because the rate is floating, this will result in a continuous depreciation in the exchange rate, and China gets less and less of the foreign currency they are trying to purchase. Also, because China exports a large amount of goods to the U.S., this depreciation will make it impossible for the U.S. to buy goods or services from China. This is not ideal for China, since their economy is still somewhat centred around exports, as is the case with most third world countries. Suddenly running out of the Dollar will undermine China’s domestic employment and output, even if the government sector can help create home demand. Thus, any shift has to be gradual.

Bad Current Account Deficits vs ‘Okay’ Current Account Deficits

In this section, I want to highlight the difference between the bad kind of Current Account Deficits and the ‘okay’ kind of Current Account Deficits.

The bad kind of Current Account Deficits are the ones that create net liabilities which are not in the domestic currency. This includes foreign currencies and commodities like gold, oil, and so on.

The Current Account is just an accounting invention; it is always balanced by an equivalent amount in the Capital/Financial Account. It does not tell you the actual external economic vulnerability of the country. What does tell you if a country is vulnerable or not, with regards to the balance of payments, is whether it can service its debts.

Local currency debts are always sustainable with respect to the Balance of Payments. The foreigners take all the risk, whether it is exchange rate risk, capital control risk, etc. So, if a country has a Current Account Deficit in local currency, issued by the sovereign, it can always be paid. If there are widespread private sector debt defaults, the government can backstop such debts as the issuer. Debts also do not ‘explode’ with a continuously depreciating exchange rate.

Meanwhile, foreign currency debts create great vulnerabilities for a country. Even modest amounts of it can cause a full-blown crisis if exports or capital inflows dry up. In my previous blog, I mentioned Greece, for a good reason. Greece essentially uses a foreign currency, the Euro, and its debt back in the 2000s was not backstopped by the ECB, making it vulnerable. Only after ECB intervention did the interest on debt stabilize, and that came at a huge cost.

Some other good examples include Sri Lanka, which had large amounts of foreign currency debt reaching 61% of GDP in 2022. I am not going to go into the details, but the fixed exchange rate of Sri Lanka created massive demand for foreign currency which the Central Bank had to satisfy. From late 2021 until early March 2022, the Central Bank of Sri Lanka attempted to peg the rupee at around Rs 200/USD, even as reserves were plunging. This turned a possibly manageable shock, arising from the war in Ukraine, OPEC price hikes, COVID-related demand shock reducing tourism revenues, as well as other COVID-related supply-side disruptions, not to mention Fed rate hikes causing a flight to the Dollar, into a full-blown balance of payments crisis.

The ‘okay’ kind of Current Account Deficit is one where the external imbalance is created by liabilities denominated in the domestic currency. There is more nuance to this, but generally, if the debt is in local currency, it can always be paid.

So, if foreigners are buying Indian government or corporate bonds in rupees, that is fine. If the deficit is being financed by FDI in capital equipment, even better, since those do not create any fixed repayment obligations and are harder to liquidate. Even if the capital inflow is in the form of ‘hot money flows’, as long as such flows are in rupees, it does not present a solvency risk. There may be a sharp adjustment in the exchange rate when the flows reverse, but it cannot bankrupt the country.

All countries cannot run Current/Trade Surpluses

It must be remembered that, by accounting, not every country can have a current or trade surplus. For every surplus, there is a deficit. For example, India’s current deficit allows it to accumulate US Dollars, which it then uses to import goods from China and oil-exporting countries. These countries run trade surpluses; our trade deficit is their trade surplus. Similarly, our capital/financial account surplus is mainly the U.S. capital/financial account deficit.

This is why it’s said that trying to achieve current or trade surpluses is fundamentally a beggar-thy-neighbour strategy. The global demand for goods and services is finite, and one country’s attempt to increase its trade surplus through internal or external devaluation usually comes at the expense of other countries; unless the deficit countries have sufficient demand, which is currently not the case and has not been since the 2008 financial crisis.

Export -led growth isn’t possible for most countries now

The IMF, World Bank, and other neoliberal institutions promote so-called ‘export-led growth,’ which involves third world countries opening up their markets to foreign competition, relaxing labour laws, and other regulations. Basically, this means allowing foreigners to exploit the country’s cheap labour and resources and transfer the gains to the first world. It is not very different from colonialism, is it?

All the countries that did succeed in ‘export-led’ growth, for example the so-called Asian Tigers like South Korea and Taiwan as well as China in the 1980s, did not follow the neoliberal policy prescription of letting the ‘free market’ run loose. I would suggest reading “Bad Samaritans: The Myth of Free Trade and the Secret History of Capitalism” by Ha-Joon Chang for more on this.

There will not be another China, South Korea, or any new export-led growth miracle. India has 1.4 billion people. The only country with a large population that succeeded in lifting domestic living standards through the export-led growth model was China, and that was only possible because of the willingness of U.S. capitalists to export their manufacturing abroad. There will not be another China. India will not succeed with ‘export-led’ growth.

So how to measure vulnerability?

In terms of Balance of Payments, the best measure of a country’s vulnerability is the amount of debt denominated in foreign currencies or commodities. This is not to say that financial claims against a country denominated in local currency are inherently invulnerable. India has seen several large outflow episodes, most recently in 2022. However, despite a rise in inflation and a fall in purchasing power, none of these events was ever a threat to the solvency of the Indian government, as it can always pay in Rupees.

Conclusion

Trade and current deficits are a terrible way to measure the vulnerability of a country, as they show both local and foreign currency balances. A better way would be to separate inflows and outflows denominated in local currency (Rupee) from those denominated in foreign currencies or commodities.

For example, you can ‘redefine’ the Current Account to include all local currency inflows and outflows. In this approach, only foreign currency capital flows remain in the Capital/Financial Account. This will automatically shrink India’s headline current deficit to near zero, since India borrows very little in foreign currencies relative to its GDP.

One might say, “this is cheating! You can’t redefine what the current account is!” I say, accounting is kind of made up. We decided what the Current Account and Capital Account mean. With a fixed exchange rate, a current account deficit actually increased the risk of Balance of Payments issues. However, with a floating exchange rate, flows in local currency, regardless of whether they are ‘capital’ or ‘current’ flows, do not present a threat to the nation’s solvency.

This new Current Account balance will show the actual vulnerability of the country. For example, for countries like Argentina and Sri Lanka, which have large amounts of foreign currency debt and where such debt payments swamp the Balance of Payments, you will see a large Current Account deficit to GDP.

Meanwhile, for a country like India, the new convention will show a very tiny Current Account Deficit, since the country borrows very little relative to GDP in foreign currencies. This measure is therefore a much better way to assess Balance of Payments vulnerabilities.