As the Rupee continues to depreciate and stabilize around ₹90/$1, parts of the financial press are bragging about how great it is that the Rupee appreciated from ₹92/$1, claiming it was because of the Government that such a thing happened.

I am against the view that the currency exchange rate has any value as information in and of itself. It doesn’t show the strength of the country; it doesn’t show the strength of the economy.

It should be clear that the Indian Government has very limited control over the Rupee exchange rate. Since India’s current account is liberalized and its capital account is mostly convertible, there is nothing preventing foreigners from trading Rupee-denominated assets. The Government can only intervene by using its foreign exchange reserves. There is an asymmetry here: the Indian Government can accumulate unlimited amounts of Dollars since it is the sovereign issuer of the Rupee. When does it do so? During times of massive capital inflows and/or very rare current surpluses.

Δ Reserves = (X – M) – NI – NT − Net Capital Flows

This is an ex-post identity; i.e., it’s only true after the fact, just like how Current/Trade/Capital accounts are ex-post.

Components of the Balance of Payments

Let’s discuss the components, I will start from the right side:

- (X-M) is, of course, Exports – Imports. Since India runs persistent trade deficits (particularly with China and oil exporters), (X−M) is typically negative. This is fine, as we will see.

- NI stands for Net Income; these include the net of dividends and interest which is mainly comprised of dividends paid to Indian entities from abroad minus dividends paid by Indian entities to abroad, since MNCs send profits they earn from the Indian market abroad.

- NT stands for Net Transfers; for India, this is a huge positive component of the Balance of Payments. This is mainly because of Remittances, i.e., Indians working abroad, especially in the Gulf, sending money home. This allows India to import more than it would be able to otherwise.

- Net Capital Flows is what it says in the name; foreigners decide to buy mainly Indian Rupee-denominated financial assets such as debt and equity. This includes Foreign Direct Investment (FDI), e.g., MNCs building plants in India; Foreign Portfolio Investment (FPI), typically called “hot money” since it’s volatile and can be squeezed down fast; and External Commercial Borrowings (ECBs) by Indian firms (which can be dangerous if not hedged properly for currency risk, but is a small component).

With Net Capital Flows, India is functionally exporting electronic entries and financial paper, mainly denominated in its own currency (the Rupee), abroad. NCF is susceptible to a squeeze in an uncertain environment, as is currently the case. Foreign traders have been net sellers throughout 2025. The thing to keep in mind is that they are selling these assets to Indians. Remember that for every seller, there must be a buyer. Since they are net sellers, the net buyers must, by definition, be Indians.

As it is clear that foreigners are able to sell, this will tell you why Indian equity markets have not been doing so well. Foreigners can sell, but as they sell, there is downward pressure on equity prices. The foreigners then sell the Rupees they obtain for Dollars. Since India has a floating exchange rate, this does not pose a solvency risk for the Indian Government. The Rupee simply depreciates.

Capital flight doesn’t exist in the same way under a floating exchange rate regime as it does in a fixed-rate one. In a fixed regime, outflows meant pressure on the peg, which forced the Government to draw down on its reserves and/or borrow from abroad. This borrowing was done in foreign currencies, which posed a solvency risk to the Government. The Government was forced.

That is not the case under a floating exchange rate regime, since every transaction implies a willing seller and a buyer. For every willing seller in the market, there must be a willing buyer for the trade to occur. Without the buyer, the foreigner simply cannot sell their assets and there is no liquidity. The traders may push the prices up or down, which shows up as appreciation or depreciation.

That finally brings us to the left-hand side of the equation: Δ Reserves. When the right-hand side is positive, the RBI is accumulating reserves. So, you can see that the RBI accumulates reserves during times of heavy capital inflows. The RBI leans against the appreciation of the Rupee since doing so would undermine trade competitiveness (remember that exports get pricier as the exchange rate appreciates). This is fine; the RBI can accumulate unlimited amounts of foreign currencies. This is how the PBOC, China’s Central Bank, accumulated trillions of Dollars of foreign exchange reserves.

So, when the RBI buys up Rupees in the foreign exchange markets (i.e., leans against depreciation), the trade deficit almost mechanically increases (all else remaining constant). This may be fine but isn’t sustainable long-term, since the RBI has a limited amount of reserves and excess intervention promotes speculation.

This was why I didn’t support the RBI’s interventionist exchange rate policies in 2022–2024. It wasn’t sustainable, as has been proven since then; it subsidized imports and capital outflows and promoted foreign currency borrowing and unhedged exposure by domestic firms (see IndusInd Bank). Excessive intervention signals to foreigners that they can exit in size without slippage (i.e., depreciation when you sell). The RBI becomes the Buyer of Last Resort for the Rupees that nobody else wants. The bragging in the financial press by certain politicians about a one-rupee appreciation is just celebrating the fact that the RBI successfully subsidized more capital outflows.

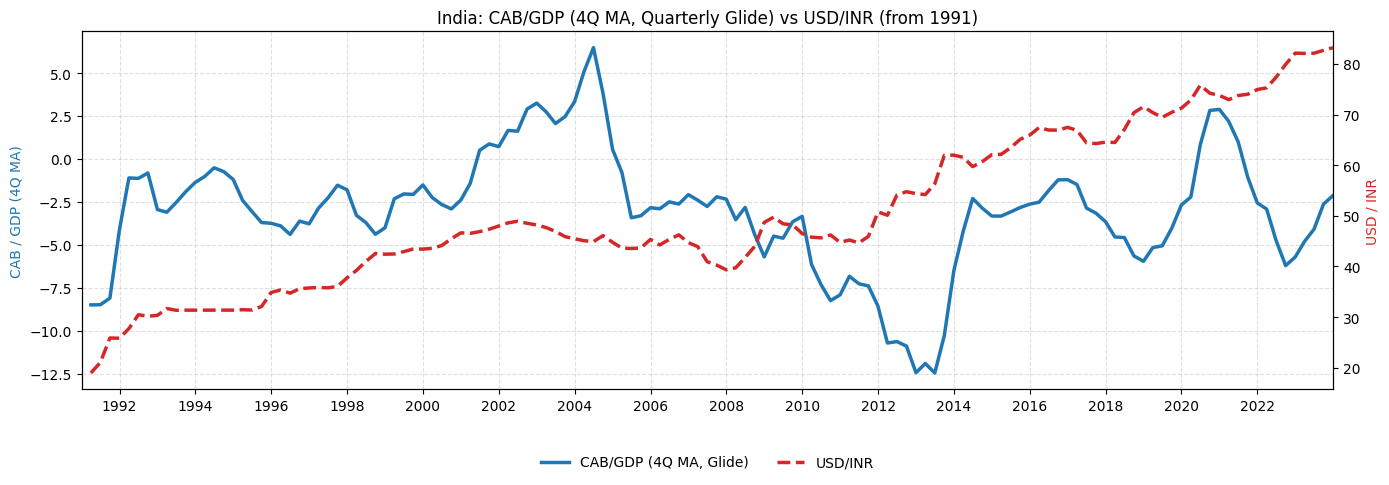

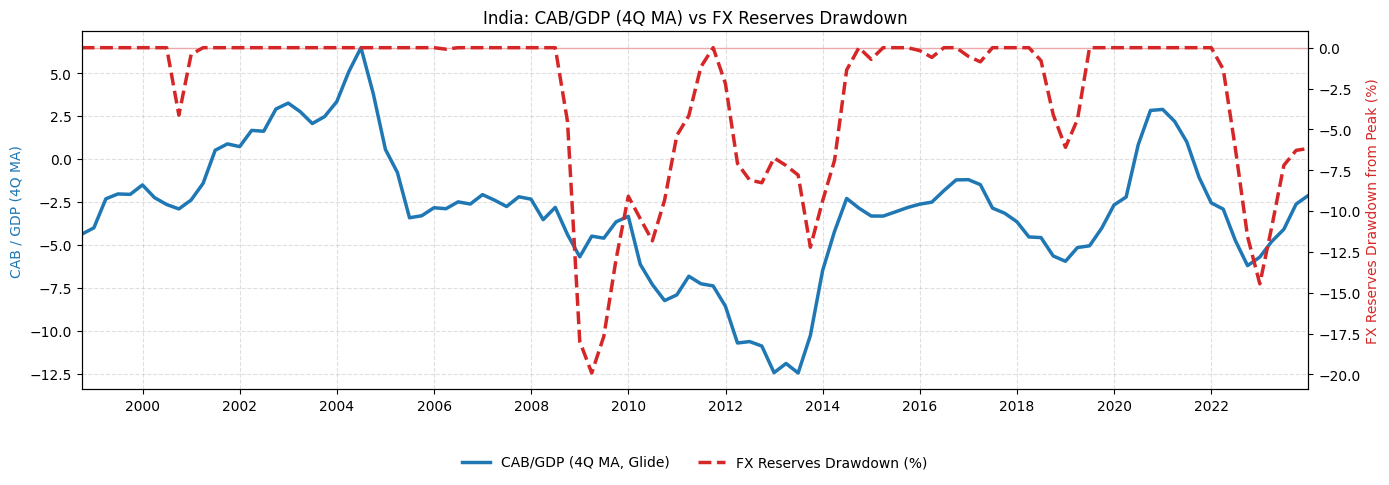

Looking at the history of exchange rates and current account deficits in India after 1991, when the Rupee was floated, we can see that when the Rupee depreciates, the Current Account is automatically compressed. This is most obvious during the 2013 Taper Tantrum, when the exchange rate depreciation automatically compressed the Current Account. The compression follows after depreciation. Usually, the sharp rise in the Current Account Deficit is at least partly due to reserve drawdown by the RBI.

This is what will happen to India now. The depreciation of the Rupee will compress imports and mildly increase exports (as exports aren’t as sensitive to exchange rate changes in India’s case). The country will lose access to real resources from abroad. Is this good? No. But it is better than cutting wages and demolishing automatic stabilizers. Oh wait—we are doing that too. Very unfortunate.

Understanding Trade Deficits

People often misunderstand what Trade Deficits are. It means the country is getting more real goods and services from abroad (imports) than it is giving. In India’s case, this exists because:

- India gets large amounts of Net Transfers in the form of remittances

- India gets Net Capital Inflows i.e. investments.

When (2) is compressed, as has been happening recently, the other major component of the Trade Deficit remains, and it increases when the currency depreciates as Indians abroad send money back home via remittances. Even if (1), for some reason, goes away because of mass deportations, this doesn’t mean India will not be able to import; it will just be limited to importing what it can export.

One can rewrite this for individual countries. India has a Trade Deficit with China because:

- India has a trade surplus with other countries (particularly the U.S.).

- India obtains transfers (the aforementioned remittances being a major component).

- India has net capital inflows (from foreigners buying mainly Rupee-denominated assets).

All these allow India to get more real resources from China than it provides to it.

When people claim “India is giving more money to China than it gets back,” you must think: who is India? It’s not the Indian Government, since the Indian Government barely has any direct trade arrangements. It is, in fact, Indian individuals and firms who do market transactions. This can only be bad if it negatively affects the public interest. Saying “they get more money” is naive since it ignores that India receives more real goods and services in exchange for electronic entries (money).

There is a valid reason to be concerned about dependency on capital flows. However, the trade/current balance doesn’t tell you anything with regard to this. One must look at where India is obtaining foreign exchange from. Remittances are the most reliable flows among these; exports, however, are vulnerable to actions by other countries (see Trump tariffs). Net Capital Flows are the most vulnerable since they depend on the minds of the investors.

However, one cannot deny that these additional components allow India to obtain more real resources from abroad than it would be able to without them, since otherwise, the trade balance would be zero.

If Trump’s tariffs successfully crush Exports, and we have no Net Capital Flows or Net Transfers, then Imports must fall by identity. The country is then obtaining fewer real resources from abroad.

One might say, how will India industrialize then? There are many tools in the toolbox: selective tariffs, subsidies, and state-owned enterprises which have the power to set prices to make goods domestically competitive. India must realize that domestic demand should be the major engine of development in the post-GFC world.

The sad part is that with Trump tariffs, developing countries are fighting amongst one another on who can export the most (global trade balances sum to zero). China is trying to counter the loss of exports to the U.S. by exporting to Asia and Europe, which undermines their productive capacity under a market-oriented system. If every developing country tries to export its way to wealth, they eventually just poach demand from each other, leading to a race to the bottom in wages and currency value.

The only good way to fight this is moving beyond market provisioning and separating manufacturing from surpluses. You can have the manufacturing sector run deficits; you can have industries cross-subsidize one another. There are many tools which aren’t being used to counter Trump tariffs and China’s industrial prowess.

That’s all.