There has been a lot of talk from certain media outlets about how Trump’s actions, like tariffs and his invasion of Venezuela etc., are a threat to the Dollar. In today’s blog, I want to help dispel that notion.

One must understand why other countries want to accumulate U.S. Dollars; the most obvious reason is to import goods and services which the country needs. But many people forget the other reason, namely that investments and exports act as a stimulus for demand-constrained economies. Not only is India exporting services to the U.S., but the sector itself provides employment to millions and props up aggregate demand.

This should be clear given the motivation behind the tariffs. Notice how countries try to retaliate against U.S. tariffs by putting an import tariff on American goods, even though imports increase the real goods and services the country receives. Why? It’s to damage U.S. markets and hence output and employment.

All these things should make it abundantly clear why the U.S. Dollar cannot be replaced any time soon. In a demand-constrained capitalist system, the export of U.S. Dollar financial claims acts as a stimulus for other economies. It is not only a tool for being able to import goods, but also a way to prop up aggregate demand.

The reason why the U.S. Dollar is the reserve currency stems not just from its military and economic might, but also the willingness (sometimes coerced) to accumulate U.S. Dollar-denominated assets.

Recently, China hit a record $1.2tn in trade surplus. Some commentators claimed this represented a loss for the U.S. because the U.S. saw a loss in imports from China while other countries gained imports from China. One must, of course, remember that trade surpluses don’t exist in a vacuum; it is by definition paid for by net transfers, net income, net capital flows, and reserve drawdown.

The question is, where did these Asian and African countries obtain the currencies needed to import goods from China so that China gets to hit its \$1.2tn trade surplus? The answer should be clear: these countries exported their goods and services, became indebted to the U.S., obtained remittances, etc.

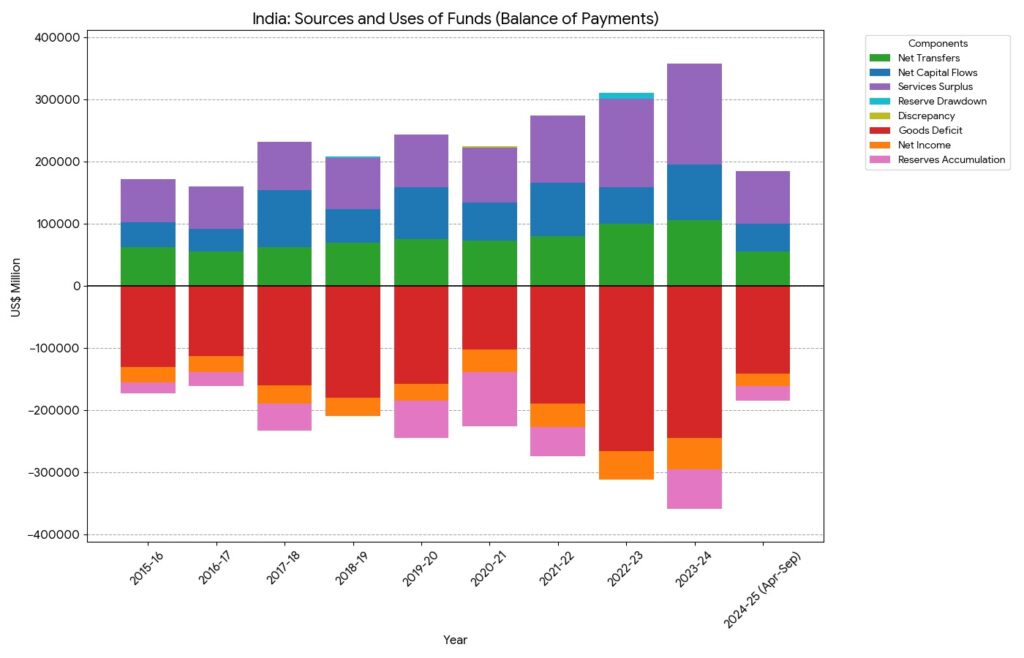

Let’s look at India. How is India’s trade deficit with China paid for? It cannot be net income or net transfers (other components of the current account), since these are either negative or very minimal w.r.t. China. It cannot be net capital flows since China exports very little Yuan to India. The answer is clear: it is financed by services exports to the U.S. and other non-China countries, remittances from abroad, as well as net capital flows, most of which come from Western countries.

You can clearly see how China hitting its trade surplus records will not be possible without the rest of the world accumulating U.S. Dollars and other first-world currencies

De-dollarization simply cannot happen until countries stop accepting U.S. Dollar financial claims. For countries having trade surpluses with the U.S., a good way to do so would be to impose controls on exports. Of course, countries do not want to do this because it will reduce their ability to import and also reduce capitalist profits and worker employment

Instead of looking at balance of payments from one-sided perspectives, e.g., ‘India has a trade deficit with China’, one must look at where the money is coming from. Trade deficits do not exist in a vacuum. By definition, a trade deficit is paid for by something. China’s export surpluses are by definition paid for by the rest of the world’s willingness to accumulate first-world currencies

Currency sources/uses vs settlement

It is also important to keep in mind that usage of Chinese Yuan or alternate currencies in international trade does not mean de-dollarization. Not even remotely. Countries can invoice trade in local currencies; they can settle trade outside the Dollar system but not threaten U.S. Dollar hegemony. Why? Because at the source (export earnings, capital inflows, remittances) and use (reserve accumulation, debt servicing, imports), there are usually Dollars.

For example, let’s say India and Russia agree to a Rupee-Ruble agreement. India really wants a lot of cheap oil from Russia; it takes Rupees and transfers them to a Rupee account held by the Russian oil exporter. Sounds fine? Sure. Until you remember Russia can’t do anything with those Rupees. They can’t use them to import from China, for instance, since China doesn’t accept Rupees in significant amounts; they accept Yuan, Dollars, or the Ruble.

So now, Russia is stuck with electronic entries. They can’t import significant amounts from India since India has very little to offer. They can try to buy shares or hold Rupee-denominated bonds, but those aren’t convertible easily either. The only way such an arrangement is possible is if the Russian Central Bank (CBR) is willing to accept the Rupees; it can always do so as the sovereign issuer of the Ruble.

We live in a world where some electronic entries are treated above other electronic entries. India’s Rupee electronic entries have low demand while U.S. Dollars have near-universal demand (other than in sanctioned countries).

India’s Balance of Payments in Sources and Uses format. By definition, India’s Trade Deficit in Goods (mainly with China and oil exporters) is paid for by its Net Transfer surpluses (remittances), Services sector surplus and net capital flows.

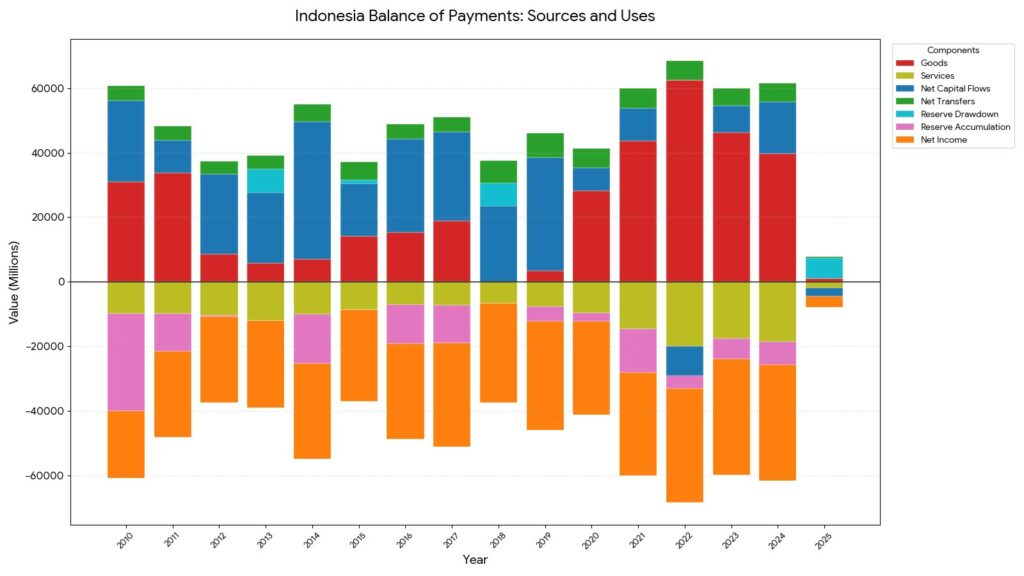

Indonesia’s Balance of Payments in Sources and Uses format. By definition, Indonesia’s goods surplus, net transfers (remittances mainly) and net capital flows pay for its net income deficit (i.e. dividends sent abroad)

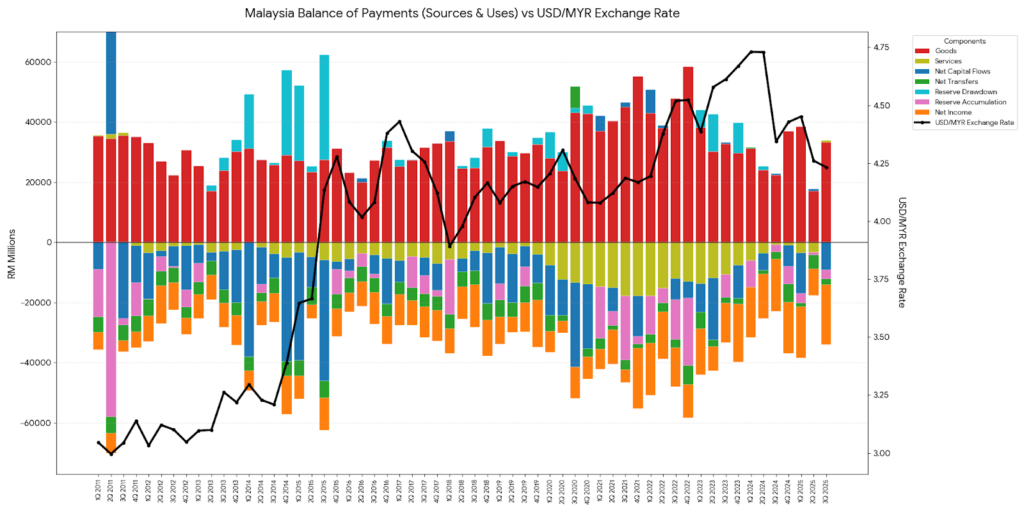

Malaysia’s Balances of Payments in Sources and Uses format. By definition, Malaysia’s goods surplus pays for its services deficit, reserve accumulation etc.

Sources and uses are probably the best way to understand balance of payments. Everything goes somewhere. Every source has a use. Whenever a country exports goods and services, it generates a financial source for someone else and a financial use for itself. Likewise, whenever a country imports, it must fund that import through some combination of income, transfers, capital flows, reserve drawdown, or debt issuance.

There is no such thing as an unfunded trade deficit or an unplaced trade surplus. By definition, every external imbalance is matched by a financial counterpart. Seeing through a sources-and-uses lens, the so-called de-dollarization efforts that focus on trade settlement don’t change much. Changing the currency used at the point of settlement does not change the underlying source of funding or the asset in which global surpluses are ultimately stored. Until those changes, the structure of the U.S. hegemony remains intact.